module-eoss-ospo101

Understanding Upstream Open Source Projects

Lesson: Introduction

Section Overview

In this section, we’ll explain what upstream means in the context of open source projects and discuss governance models, and their effect on your contribution strategies.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you should be able to:

- Describe what an upstream open source project is and why it’s important

- Explain some typical governance models and strategies for successful contributions

Lesson: Introduction to Upstream Open Source

What Do We Mean by Upstream?

We’ve used the term upstream already in this module, but what do we mean by that?

Here’s a quick definition:

Upstream (noun)

The originating open source software project upon which a derivative is built

This term comes from the idea that water and the goods it carries float downstream and benefit those who are there to receive it.

To upstream (verb)

A short-hand way of saying “push changes to the upstream project”, i.e. contribute the changes you made to the source code program back to the original project dedicated for that program.

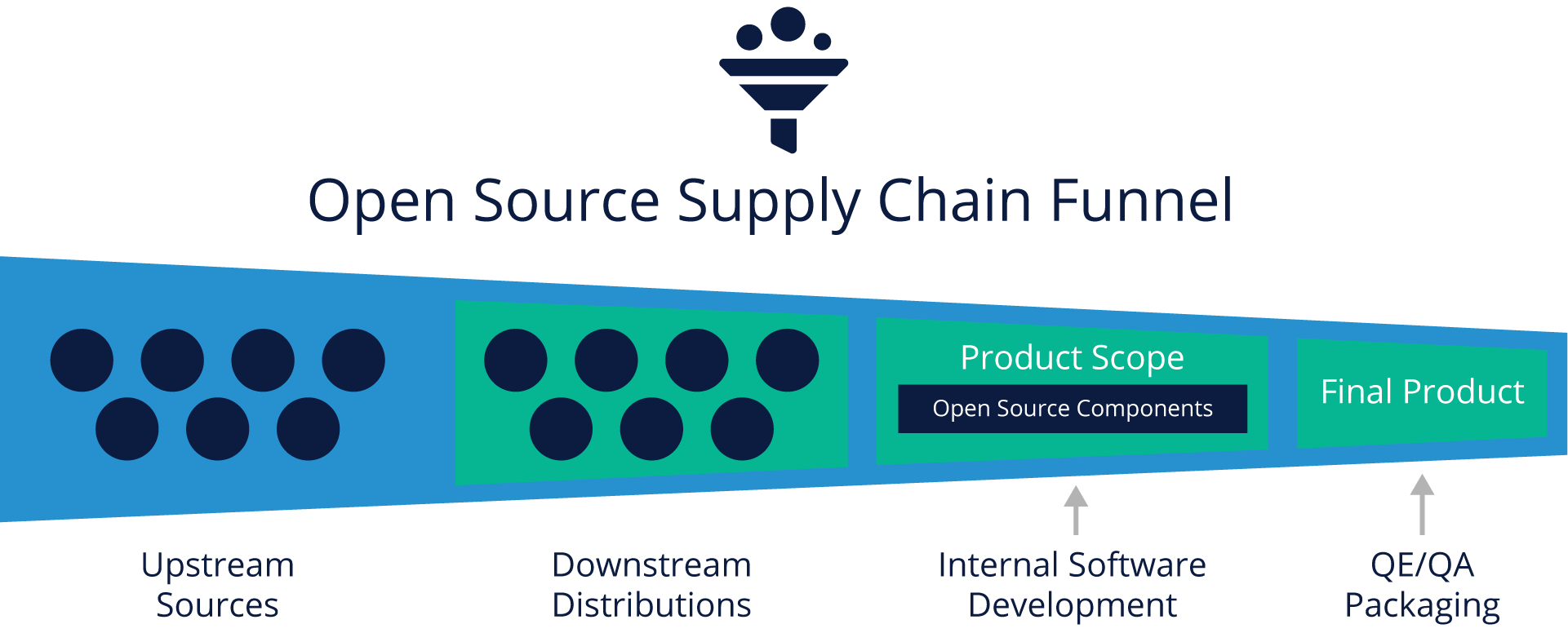

If you think about upstream in the context of a supply chain, it would like like this:

Why Should You Contribute Upstream?

The biggest question often asked by organizations is why even contribute upstream to begin with. While it may seem easier to just consume and never contribute back, there are many reasons why you should consider making the effort to contribute, including:

- Private code is never considered in public development

- Integrating your changes upstream means others are aware of them, and can plan for and around them

- Reduces the risk of accidental breakage in your own code - if you make local changes which are incompatible with the upstream project, it takes time and resources to fix those issues

- Integrating changes into an upstream project reduces the amount of effort to build a finished product

- Contributed code is reviewed and may attract external resources to changes you’ll need in the upstream project

- Contributions strengthen the project and give you an opportunity to influence future project directions

When Should You Contribute Upstream?

Organizations new to open source often struggle with when the right time is to start contributing upstream. The following guidelines give a good overview of reasons/timing for upstream contributions:

- When the costs (time or $) of keeping your code in sync with the upstream project exceed the convenience of working alone

- When you want your code to be used by others (including customers)

- When you want your code to become a defacto standard, or drive adoption of the mainline project

- If you anticipate relying on a certain codebase repeatedly in upcoming products that complements the upstream project

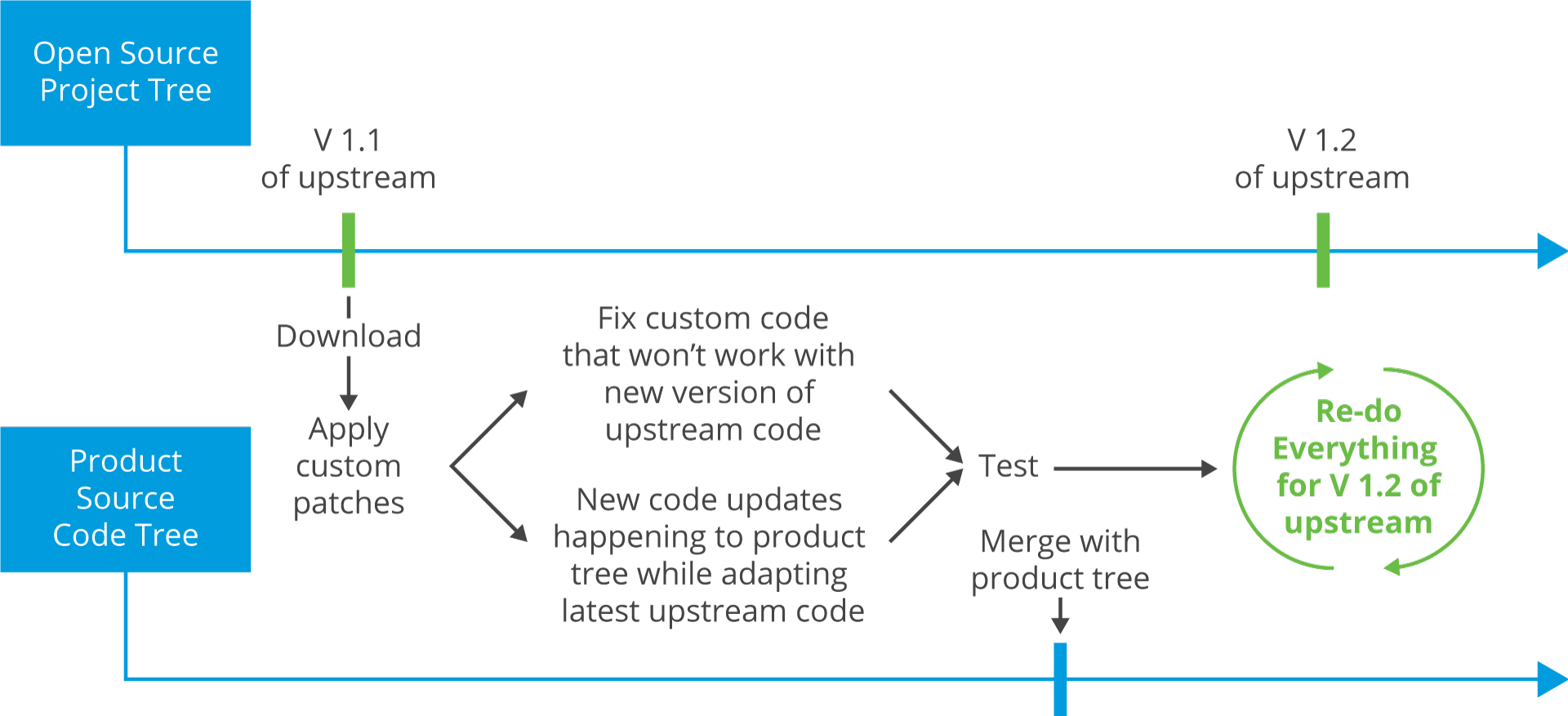

Example: Development Without Upstreaming

To give you a better perspective on what can happen if you don’t effectively participate in an upstream project, here’s a graphical example:

As you can see, it can become quite burdensome when you need to bring in the “mainline” of an upstream open source project, for example when a security bug or feature that you need is released. Keeping up with major releases of an upstream project on a regular basis means that you are paying that cost incrementally, instead of all at once.

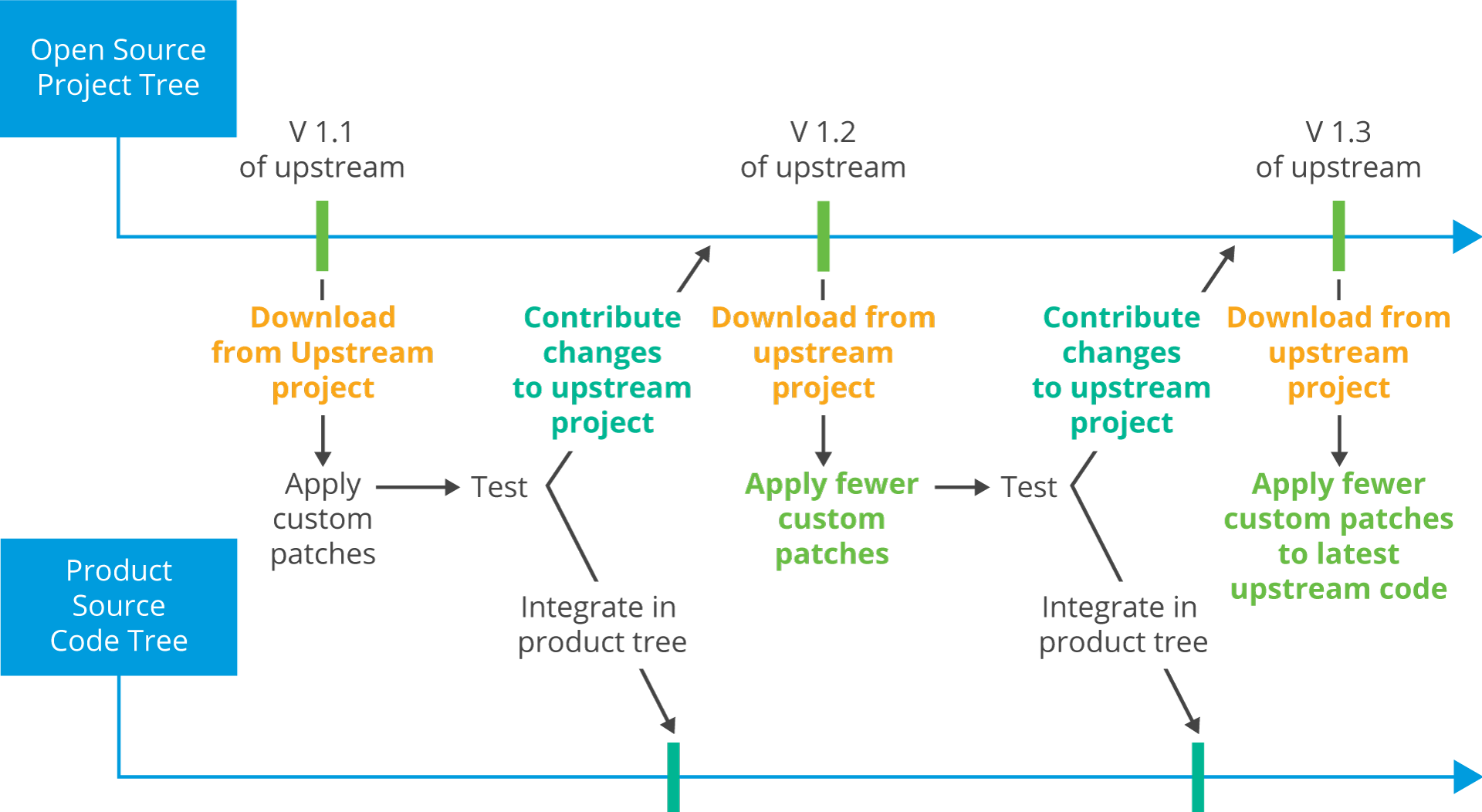

Example: Development With Upstreaming

As a counter-example, here’s what development looks like with an effective upstream contribution strategy:

The important thing to note here is the application of fewer custom patches because problems and integration issues can be found more quickly when making frequent upstream contributions and keeping better in sync with the upstream project.

Upstream Governance Models

There is no shortage of governance models used by upstream open source projects. They differ according to the degrees of centralization, strong influence by one or a few organizational entities, and existence of democratically-inspired decision mechanisms and leadership selection.

The choice of model and how well it is executed have profound influences on the quality of a project, as well as how quickly it is adopted and evolves, improves and succeeds. There is no one-size-fits-all model and each has its advocates and detractors. Furthermore, different projects have different inherent needs, which may be better satisfied by one particular model.

In the following pages, we’ll cover the most often used governance models.

Company Led Governance

Company-led projects have a mostly-closed process with the following characteristics:

- Development is strongly led by one corporate or organizational interest

- One entity controls software design, releases

- May or may not solicit contributions, patches, suggestions etc.

- Internal discussions, controversies, may not be aired very much

- Exactly what will be in next software release not definitively known

- Upon release, all software is completely in the open

Examples: Google Android, Red Hat Enterprise Linux (RHEL)

As you can imagine, it can be hard to influence direction of these projects except by making contributions to projects further upstream from these efforts - for example, the Linux kernel is upstream from both Google Android and Red Hat Enterprise Linux and getting features accepted there (if appropriate) is one way to influence Android and RHEL.

Benevolent Dictator

Projects with this type of governance typically have the strong leadership of one or a few key individuals. They also have the following characteristics:

- One individual has overriding influence in every decision

- Project’s quality depends on that of the benevolent dictator(s)

- Can avoid endless discussions and lead to quicker pace

- As project grows, success depends critically on dictator’s ability to:

- Handle many contributors

- Use a sane, scalable, version control system

- Appoint and work with sub-system maintainers

- Benevolent dictator’s role may be social and political, not structural: Forks can occur any time

- Maintainers write less and less code as projects mature

Example: Linux kernel

Governing Board

Projects with a Governing Board structure have the following characteristics:

- A body (group) carries out discussions on open mailing lists

- Decisions about design, release dates, etc., are made collectively

- Decisions about who can contribute, how patches and new software are accepted, are made by governing body

- Much variation in governing structures, rules of organization, degree of consensus required, etc.

- Tends to release less frequent, but hopefully well debugged versions

Examples: FreeBSD, Debian

Projects with this form of governance can be composed of either hobbyists or corporate developers, but tend to have less overt corporate influence than the Foundation/Consortium model (covered next).

Foundation/Consortium

Projects within Foundations or Consortiums have a mix of the previously-discussed governance models, usually with the following unique characteristics:

- Business/strategic governance oversight committee/board

- Provides overall business and strategic direction

- Membership usually composed of corporate sponsors of the project

- Separate technical steering committees for technical decisions

- Public decisions/mailing lists for technical discussions

- Leadership composed of technical resources of corporate sponsors

- Ability to have non-corporate-affiliated technical resources appointed/voted on

- Regular releases with longer testing/acceptance cycles

Examples: Open Stack, Kubernetes, Academy Software Foundation

We’ll have more to say about Foundations and open source partnerships in a future training module.

Participation Considerations

Many people ask which of the governance models above is best or which should their organization participate in. The reality is that each model has advantages and disadvantages, but in many cases, you may not have a choice of which model to participate in, especially if the project is one that is core to your product or business.

The biggest thing you should consider as an organization is making sure that you have the proper staffing (engineering and leadership) to participate effectively in whichever model the project you need is using. The biggest challenge many organizations face is participating with either too many or two few engineering or management resources.

Understand what your organization needs from a project - if you need strategic input, making sustained engineering contributions as well as monetary support or leadership may be your best bet. If you are primarily a consumer of the technology with only the occasional need to make upstream contributions, having a primarily engineering-driven resourcing approach may work better.

Section: Effective Upstream Contribution Strategies

Lesson: Introduction

Section Overview

In this section, we will discuss how to most effectively work with upstream open source projects, including understanding the best ways to engage with development communities, strategies for success, and what behaviors to avoid.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you should be able to:

- Describe the most important factors in working effectively with upstream communities

- Explain best practices for successful upstream contributions

- Understand what processes and considerations you’ll need to address in your organization to be an effective upstream contributor

Lesson: Upstream Collaboration

Where to Contribute

After understanding why it’s important to contribute to upstream projects, the next most important determination is finding out where you should be contributing. As we covered in Module 2, Open Source Business Strategy, having a clear understanding from both an engineering and business perspective about what open source projects are important to you will help guide you in this important decision.

In general, you should be evaluating open source projects, and your contributions, based on what provides the most overall value for your organization, for the amount of engineering resources you’ll have to spend to enable these contributions.

Some important questions and considerations include:

- Which open source projects do we use within the organization? Take some time to assess which open source projects are already in use across the entire organization to determine which ones are strategic to your business. A few places you might want to focus your assessment: critical business infrastructure (operations), development and deployment tools that impact your ability to release products, and software that is important for customer-facing products or services.

- Which projects should we target for contribution? Most organizations use many open source projects, so it’s important to make sure that your plan focuses on just the most important ones. Just because a project isn’t on the target list doesn’t mean that people can’t contribute to that project; it just means that it isn’t a critical focus for your organization. If an open source project is critical to your business and has the potential to cause significant downtime or disruption to your ability to serve your customers, it’s probably a good candidate for contributions.

What to Contribute

Other than where you should be contributing to upstream projects, one of the most important questions to ask is “Why are these contributions important?”

It’s easy to jump in and start talking about all the great things you plan to do, but don’t forget to include compelling arguments for why this work is important and strategic to the organization, as well as how you plan to parlay any and all contributions into strategic value.

Sometimes the contributions are important to supporting a product you are building, and sometimes they are important just to keep the overall upstream project strong and healthy so that you can rely on it in your downstream efforts. You also need to consider this from the upstream project’s point of view - your planned contributions need to be valuable to the wider community for the upstream project.

It’s important to avoid the bad behavior of proposing contributions that may be strategic for your organization, but only useful for your own use cases, and not generally applicable to the whole upstream project community.

How to Contribute

There are many great resources for the technical process of how you contribute to upstream open source projects, but, let’s concentrate at a high level here on some best practices you can use when considering how your organization will contribute.

Here are some things to consider as you start your contribution journey:

- Adopt an “upstream first” philosophy

- Always plan to merge back with the main branch

- Forks and side branches are ok as long as there is a plan to merge with upstream

- Align internal development effort with the upstream branch release cadence

- Require all code to be properly documented to be better understood by upstream reviewers, which will likely contribute to a faster acceptance cycle

- Follow the release early and often practice. Don’t build a huge code base and then decide to upstream it. Share design, early code and submit large contributions in smaller, independent patches that build on each other.

- Track the code you choose to not upstream: Reevaluate at every opportunity. If you spot an upward trend in the internal maintained code’s size, this calls for a discussion and reevaluation of prior decisions.

Effective Contribution Policies

Though it’s important to have effective compliance policies implemented as part of your open source strategy, it’s also critical that your legal & leadership teams be involved to help set up lightweight policies of fast approval of upstream contributions.

These policies should be less about rules and regulations and more about helping people be successful in making contributions to open source projects. It can help if people have guidelines and checklists to make sure that they have everything they need to make a successful contribution without running into licensing or confidentiality issues.

Especially for new contributors, it can also help to have an internal review process available as a safe place to get feedback before making a contribution.

In many cases, contribution policies have predefined lists of approved open source licenses used by upstream projects, and take a “sandbox” approach with developers, where they are allowed to contribute to upstream projects if they are doing so for a project using one of the pre-approved licenses.

The goal is to balance corporate governance of open source with a process to facilitate interactions with upstream developers.

Staffing Considerations

Staffing is a critical element to successful upstream contribution. You may already have relevant expertise in your organization, if you have engineering teams that have made some small upstream contributions. However, as you start to look at upstream projects that are critical for your business, you’ll need to ascertain whether you have the relevant expertise in-house to make sustained contributions, or whether you need to hire for it.

If you have to hire externally, it’s important to make sure to find people with the skills not only to produce the contributions, but also people who are skilled at getting their upstream contribution accepted by the community.

One way to seed your hiring is to consider hiring key developers and maintainers from the upstream project community. Be aware that these people are in high demand, so you have to be prepared to offer not only an appropriate salary, but also an engineering culture that allows them to continue working on the upstream project that they are a part of.

The goal is to find people who have enough peer recognition to be influential in the community. There are typically three pillars to this: domain expertise, open source methodology, and working practices. You also need to align corporate interests with individual interests: it’s very hard to motivate a senior open source developer to work when their personal interests don’t meet with corporate interests in a given project. For example, a Linux memory management expert may not be interested in working on file systems, a corporate priority. Therefore, finding a match in interests is critical for a long lasting relationship.

Schedule/Timing Considerations

Providing adequate time in project schedules for upstream contributions is essential. If you have internal developers who are making upstream contributions, you’ll need to budget time in their schedules to allow for these contributions to be made. If you are hiring external open source developers into your organization to work upstream, and also work on your product, you’ll need to consider how to balance their schedules as well.

The core principle for hiring open source developers is to support your open source development and upstream activities. There is also the expectation that they should support product teams in their expertise areas. However, it’s not uncommon for product teams to exercise their influence in an attempt to hijack the time of the open source developers by having them work on product development as much as possible. If this happens, many open source developers will head to the door, seeking a new job that allows them to work on their upstream project before you realize what just happened.

Therefore, it’s important to create and maintain a separation of upstream work and product work. In other words, it’s recommended to provide your open source developers with guaranteed time to meet their upstream aspirations and responsibilities, especially if they are a maintainer. For junior developers or other internal developers who are using open source in product components, such interactions with the upstream community will increase their language, communication, and technical skills.

In the absence of such an upstream time guarantee, it’s easy for these team members to be sucked into becoming an extension of product teams, resulting in their upstream focus drying up in favor of product development, which may help in the short term, but can ultimately lead to loss of your organization’s reputation in the upstream community, which can negatively affect your ability to help guide the upstream project in areas beneficial to your organization.

Training Considerations

Even if you hire the best outside open source developers, you’ll need to consider providing training opportunities for your existing engineering staff, as working with upstream communities can be a very different experience than they may have been used to in the past.

What are some of the kinds of training you should be considering?

- Best practices for making upstream contributions

- General training on open source, licenses, governance, etc.

- Training on conflict resolution or dealing with challenging people

To scale your efforts over time, include in your training plan some programming that provides experienced open source contributors as mentors for new contributors. Mentoring is a powerful way to grow open source talent in specific technology areas relevant to your products.

It’s easy to hire a few resources from outside the company, but there are several limitations to this approach. The alternative approach is to convert your existing developers into open source contributors via training on the technical domain and open source methodology. These developers can then be paired with a mentor to further expand their skills.

Set up a mentorship program where senior, experienced open source developers provide mentorship to junior, less experienced developers. Typically, the mentorship program would run for 3 to 6 months; during this time, the mentor should supervise the work of the mentee, assign tasks, and ensure proper results. The mentor would also do code reviews for anything the mentee produces, and provide feedback before the mentee pushes the code to the upstream project.

The goal is to increase the number of developers the company has contributing code to the upstream project, and to improve individual effectiveness by increasing the quality of code and the percentage of code that is accepted into the upstream project. Generally speaking, no more than 4-5 mentees should be assigned to a given mentor, and ideally they should work in the same area as the mentor to make code reviews more efficient.

Tooling Considerations

It’s important to provide a flexible IT infrastructure that allows developers to communicate and work with the open source community without any challenges. Additionally, you should consider setting up internal IT infrastructure that matches the tools used externally by upstream communities. This helps to help bridge the gap between internal teams and the upstream project community.

Much of this infrastructure will naturally evolve with your organization’s open source culture, but it’s important to be aware of the necessity and plan for its implementation. There are three primary domains of IT services that are used in open source development:

- Knowledge sharing (wikis, collaborative editing platforms, and public websites)

- Communication and problem solving (mailing lists, forums, and real-time chat)

- Code development and distribution (code repositories and bug tracking)

Some or all of these tools will need to be made available internally to properly support open source development. There is a chance this might conflict with existing company-wide IT policies. If so, it’s vital to resolve these conflicts and allow open source developers to use the tools they are familiar with. These open source practices typically require an IT infrastructure that is free from many standard, limiting IT policies.

Other Forms of Contribution

Remember that upstream communities also need other kinds of support that may not be code related. Look at the governance models for the projects you’re interested in to determine whether there is an option for corporate membership or sponsorship for the project or the foundation responsible for it. This provides funding to help the project be successful, and in some cases, it can help your organization get more involved in an advisory role or provide some influence into the project.

In addition to funding projects directly, consider sponsoring related conferences. These can be great for getting the word out about your work and for meeting people who you might want to recruit. In particular, don’t overlook your participation in local user groups where you have employees. Sponsoring those local groups and sending contributors to give talks can be a great way to recruit local people who are passionate about particular open source projects.

Evaluating your Upstream Efforts

Because you are making a significant investment in time, people and money, it’s important to consider how you are going to evaluate your upstream efforts. You can track non-code contributions like sponsorship dollars in the standard way you would any accounting investment, but you should give considerable thought to tracking contributions for projects you care about.

Contributions can include upstream code development, supporting product teams, knowledge transfer (mentoring, training), and visibility (publications, talks).

There are several toolkits that help track source code contributions; for instance, The Linux Foundation uses a tool called gitdm, which produces the data reported in the Linux Foundation yearly Linux Kernel report. This can be used to track both individual developers as well as the overall team performance. Individual developers can be tracked for the number of patches they submit, the patch acceptance rate (patches submitted divided by patches accepted), and the type of patch (e.g. if it is a new feature, enhancement of existing functionality, bug fix, documentation, etc.).

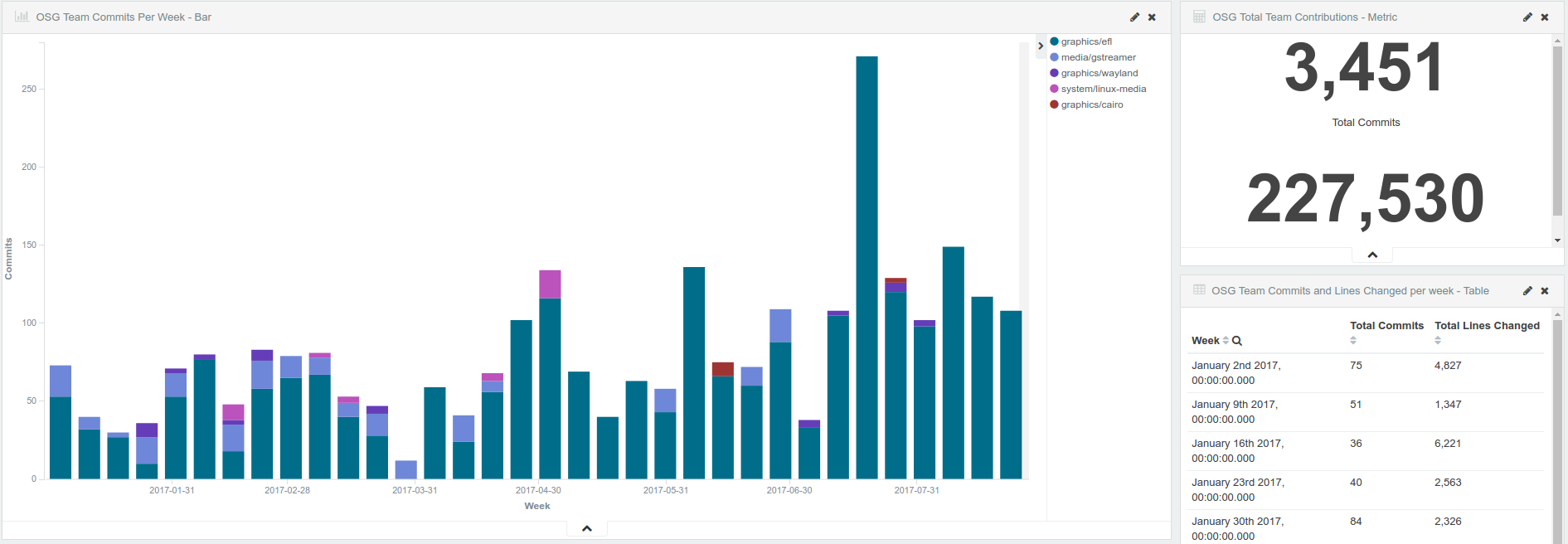

Other tools like GrimoireLab can also be used to chart and visualize the metrics you want to track. See the next section on metrics for specific examples of what you should track.

Metrics for Tracking Progress

Once you start implementing these open source best practices, you’ll need proper open source metrics to drive the desired development behavior. But the traditional metrics often used in product organizations don’t apply in the context of open source development.

For example, tracking the number of changesets or lines of code can be a good metric for open source development impact. But you may have multiple instances of desired functionality being implemented upstream because your open source developers lobby for support from the community. In this case, the number of changesets or lines of code doesn’t matter nearly as much as the technical leadership that team members provide to get code upstream and reduce the company’s downstream maintenance efforts. So the metrics you track should account for both activities.

Commits and lines of code over time

One of the most basic things to track is the number of commits and lines of code changed over a specific period of time, such as every week, month, or year.

The total commits and lines changed per project per week is a good place to start tracking metrics.

With this data, you can compare contributions from various internal development teams to identify where source code contributions are coming from and help ensure that resources are allocated appropriately.

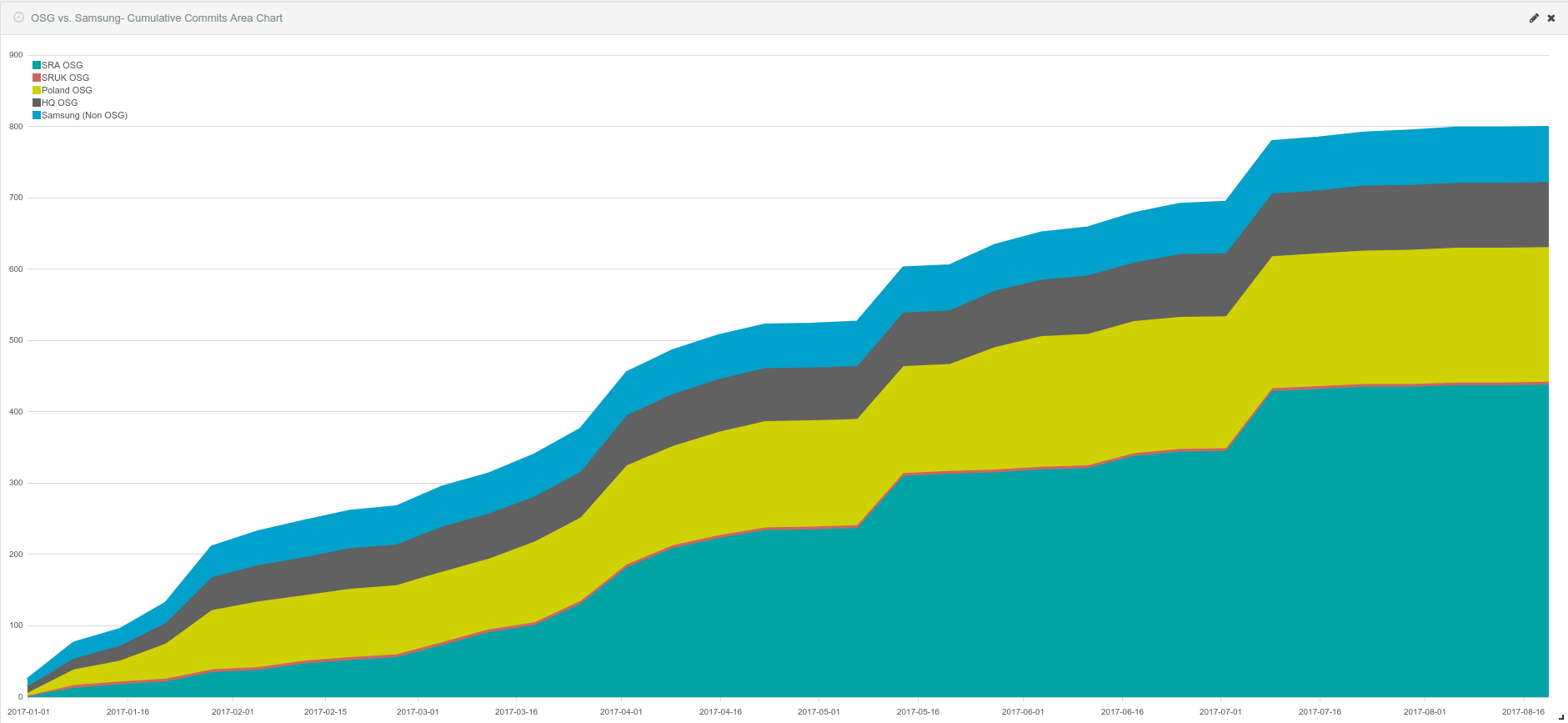

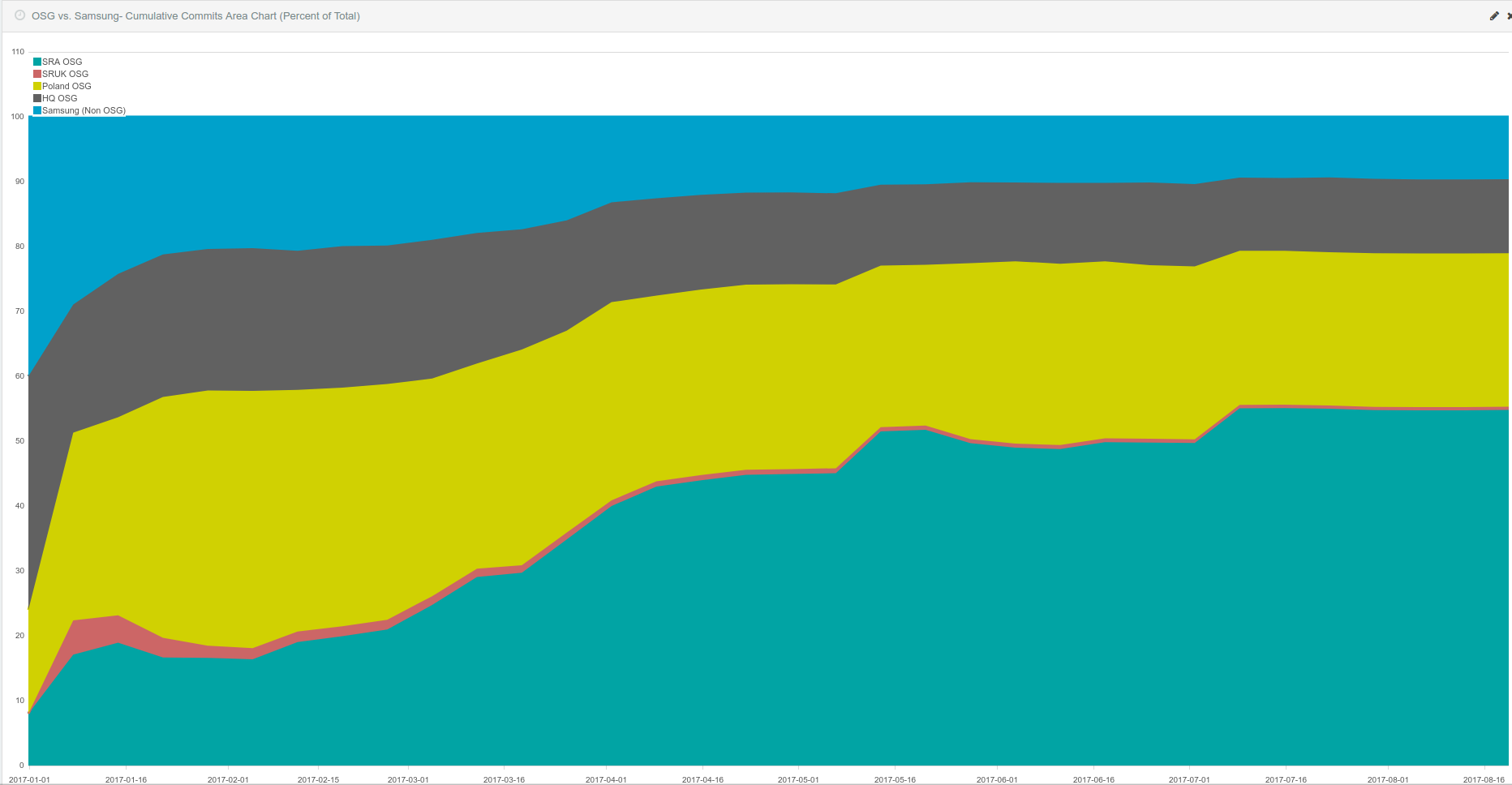

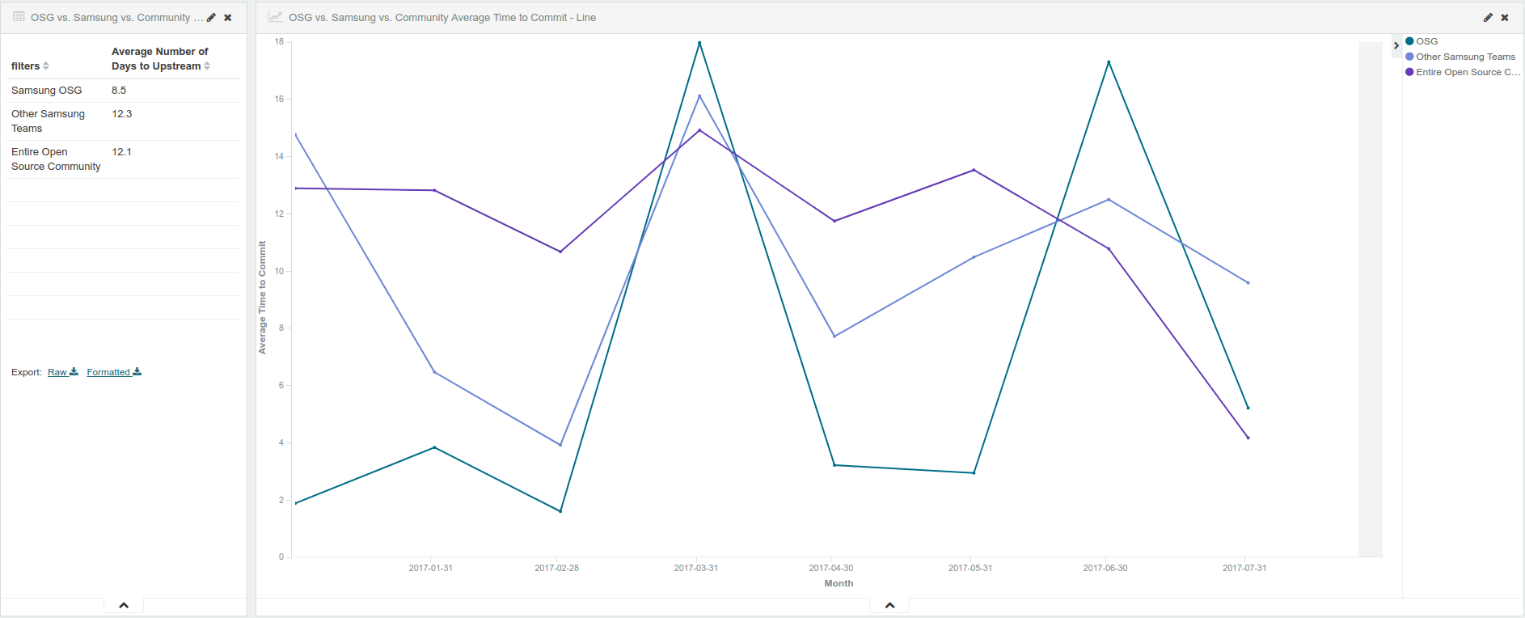

From here you can create charts that compare various internal teams for their cumulative contributions, percent of total contributions, and the amount of time it takes to get code committed upstream (see the following charts).

Figure 2: Cumulative contributions over time can be tracked to compare internal teams and identify teams that are increasing their involvement in a particular open source community (in this chart, it’s the Linux kernel).

Figure 3: Displaying your company’s contributions as a percent of total over time allows you to identify the teams that contribute the most code.

Figure 4: The amount of time it takes to commit code upstream can be valuable for tracking your development efficiency. This table and chart shows how quickly various teams are getting their code contributed upstream and compares it to the community as a whole.

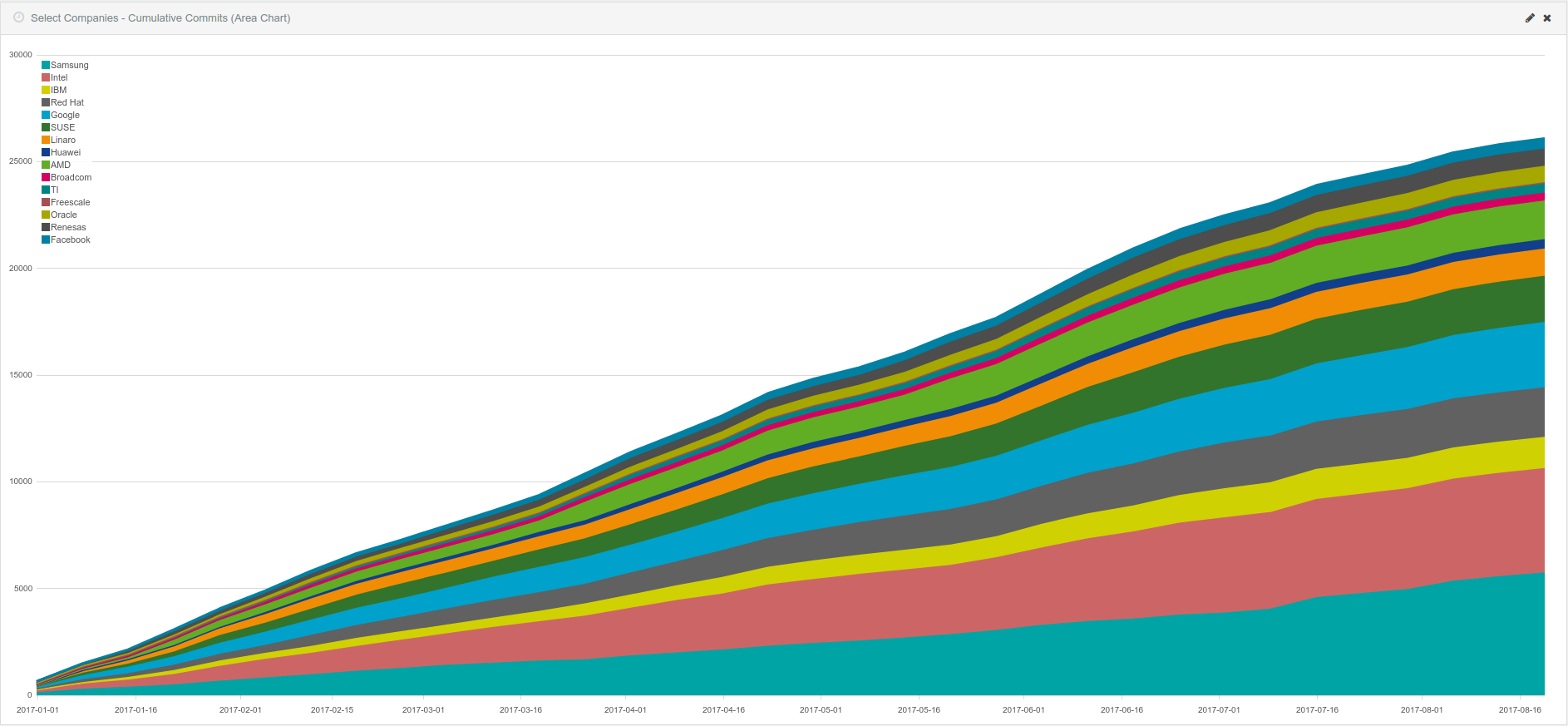

You can also use these metrics to compare your performance to other companies who are involved in the Kernel ecosystem for instance (Figure 5). This competitive analysis helps you be better informed about the overall developer ecosystem for the project.

Figure 5: Cumulative contributions can be sorted by company to see how your company stacks up against others.

These metrics provide a much better idea of where your strengths and weaknesses are and can help inform your overall development strategy. Tracking your own contributions relative to competitors’, for example, provides valuable information that helps an organization position its products relative to competitors’ in the marketplace.

Being a top contributor isn’t a goal, in and of itself, but rather an indication that the organization’s development efforts are being accepted by the communities in which it participates.

Things to Remember

We’ve presented a lot of information so far about working most effectively with upstream open source projects. We’ll try to distill this down to some key things to remember:

- Establish a policy and process to guide open source contributions

- Set up a team to oversee approvals for all open source contributions

- Focus contributions in the areas that will enable your technologies

- Provide the needed IT infrastructure and tooling for contributors

- Offer training to your staff on contribution best practices

- Track contributions, measure impact, improve, and communicate

- Establish a mentorship program to train less experienced developers

- Provide contribution guidelines, how-to’s, do’s and don’ts

- Make open source legal support accessible to developers

- Hire from the open source communities you value the most

- Always follow the community processes and practices specific to each project

- Always consider if what you’re upstreaming is valuable to the whole community, and isn’t a specific case just for your product

Section: Upstream Development Practices

Lesson: Introduction

Section Overview

In this section, we will look in more detail at the development processes and practices used by most upstream projects, to help give you practical guidelines on how to implement the contribution strategies we discussed in the previous section.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you should be able to:

- Describe the overall process for how to make upstream contributions

- Explain how to best align internal processes for better upstream collaboration

Lesson: Process Overview

Before You Begin

After you’ve identified the projects you’ll need to contribute to, spending a little time understanding the project’s inner workings (including governance, as mentioned previously) will be helpful. Here are some ways to begin:

- Follow the project discussions (mailing lists, IRC, Slack, discussion forums) to understand ongoing efforts

- Who are the core developers?

- What are areas of high priority?

- How do release cycles work?

- What are the major bugs currently outstanding

- Experiment with latest stable and experimental releases

- Determine how your interests and priorities align with those of the project

- Find others in the community who share your interests and priorities, and work with them

Signal Intent

It’s important to communicate with the community about what changes you are planning to submit. The process typically starts with sending a message to the community through whatever mechanism they are using.

This public discussion is a prerequisite and helps make maintainers aware of the need and the problems you are working to solve. It can often help you recruit others to help do the work, as well as let you gather feedback on the usefulness and design considerations before doing a lot of work (and having your change rejected).

As you propose your change, keep these important things in mind:

- It should be useful to others and not just to your specific usage models

- It should be implemented in small parts, and delivered in a way that provides immediate benefit

- It should be backed by resources ready to implement and maintain it within your organization

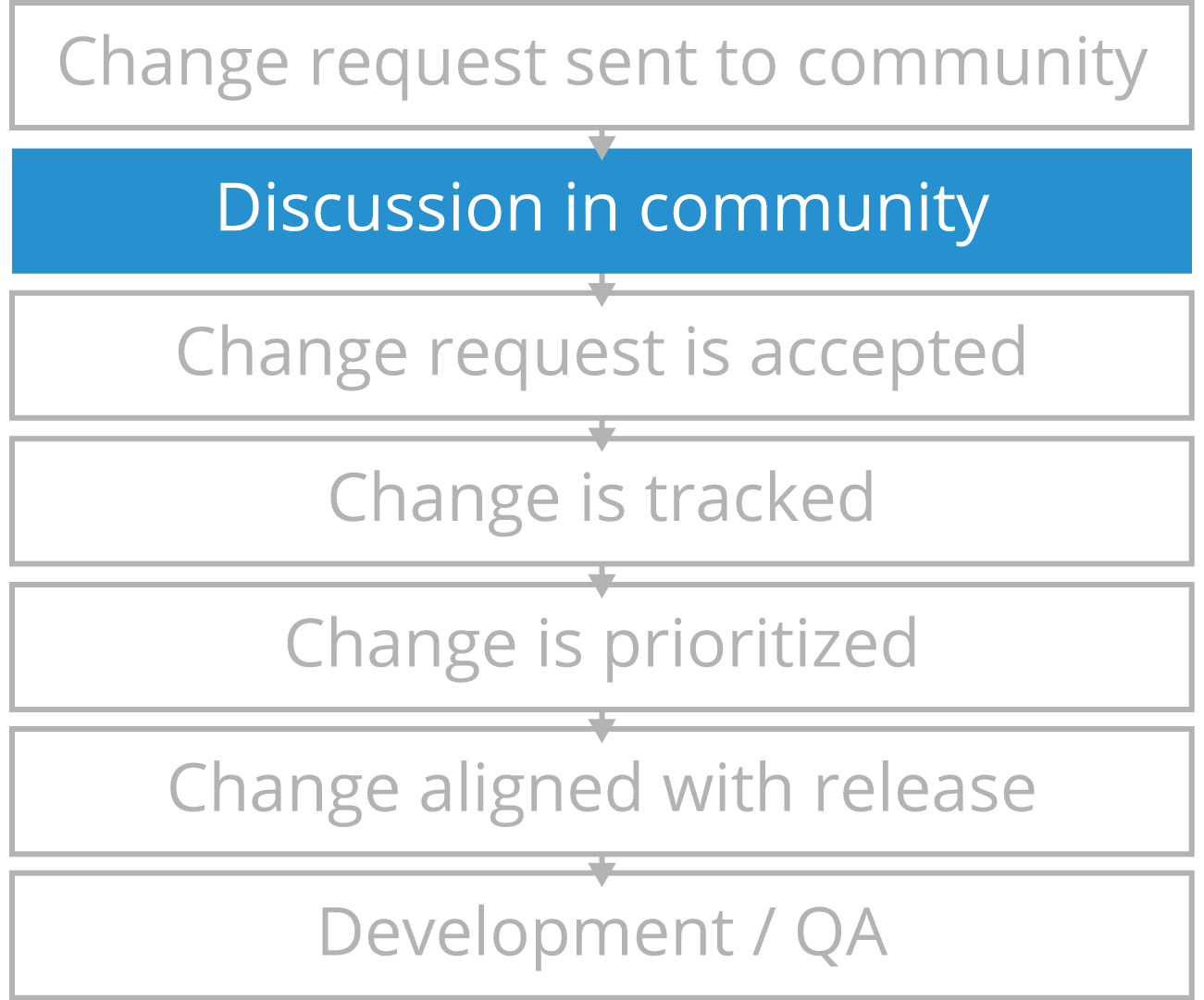

Discussion and Rationale

After a change request has been submitted, there is often some form of discussion in whatever tool the community uses for primary communication. At this time, it gives other interested parties an opportunity to comment, provide feedback, critiques, and it also gives maintainers an opportunity to comment on whether the project is ready to accept such a change.

The comments at this stage could range from brief approval to detailed questions about implementation, especially if the change is considered high-risk or potentially intrusive to core parts of the project. It’s a good idea to have some thoughts about how you want to convince others and address potential challenges you may see when you first send this communication.

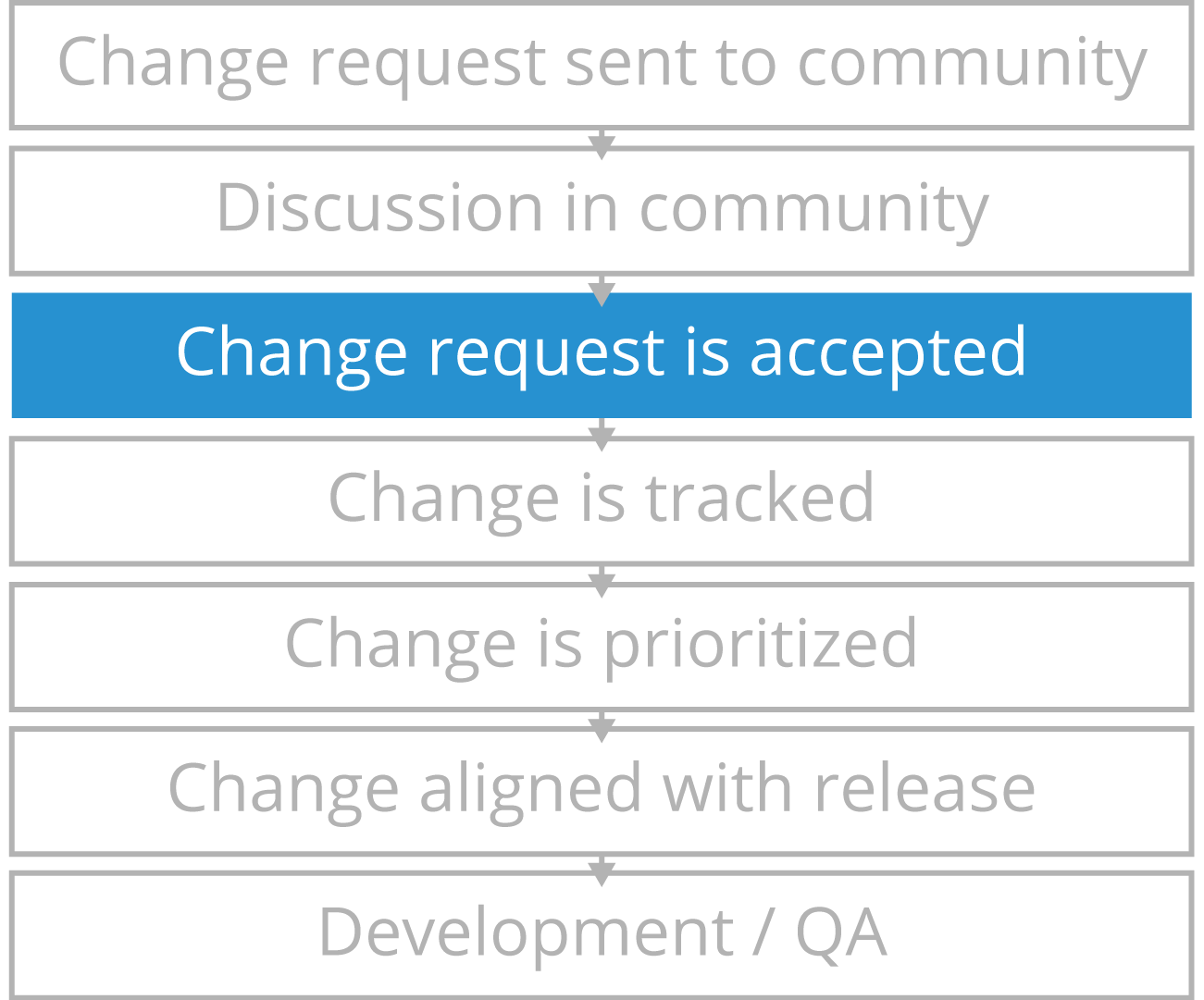

Acceptance

After the community discussion, if the maintainers and other interested parties agree, the change is accepted, and some additional considerations are debated, including ascertaining how strategic the change is to the project, an indication that the proposed implementation seems ok, and general consensus that the change is unlikely to affect stability, security, or overall functionality of the project.

One or more of the project maintainers will usually signal their approval at this phase.

Tracking Proposed Contribution

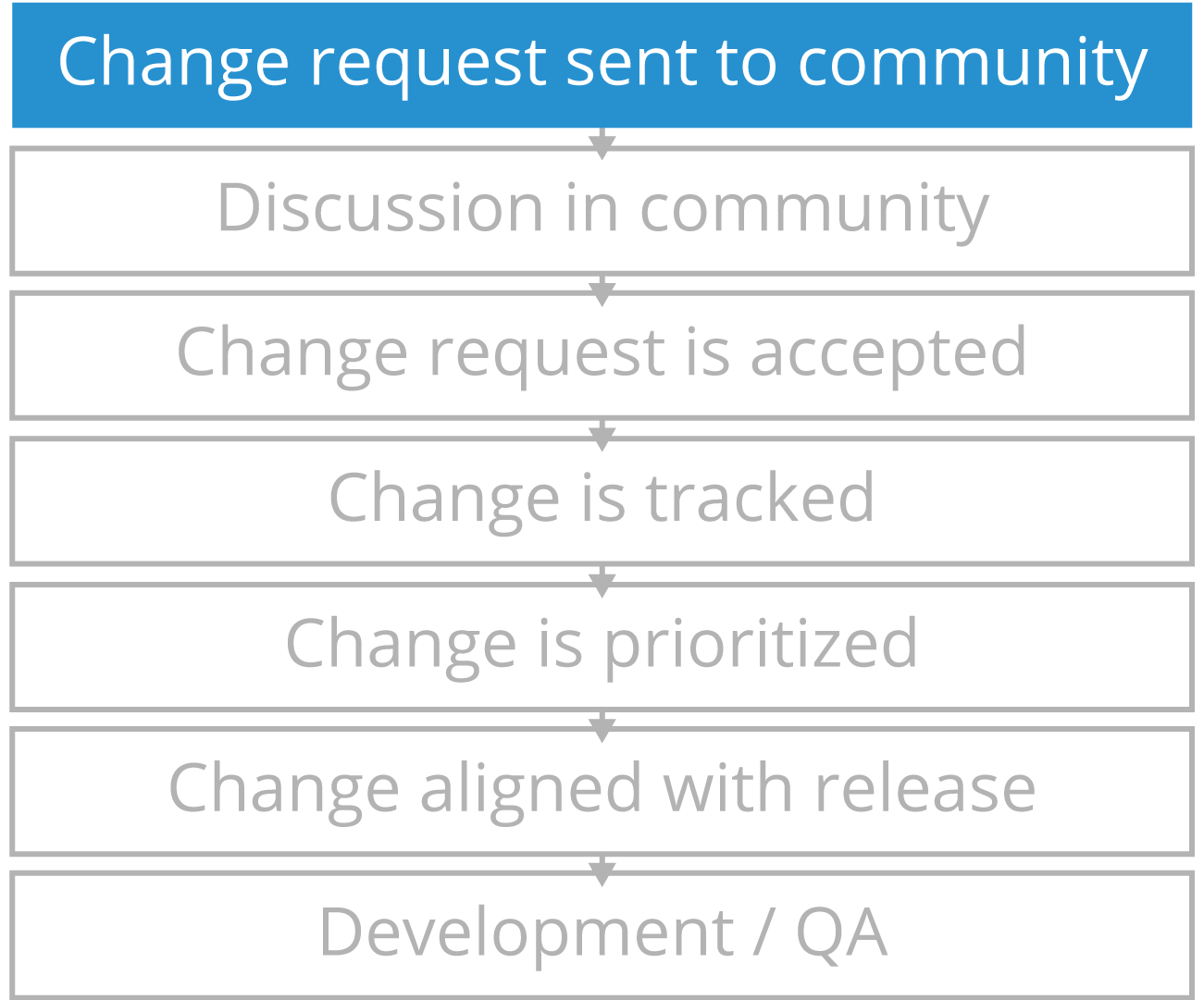

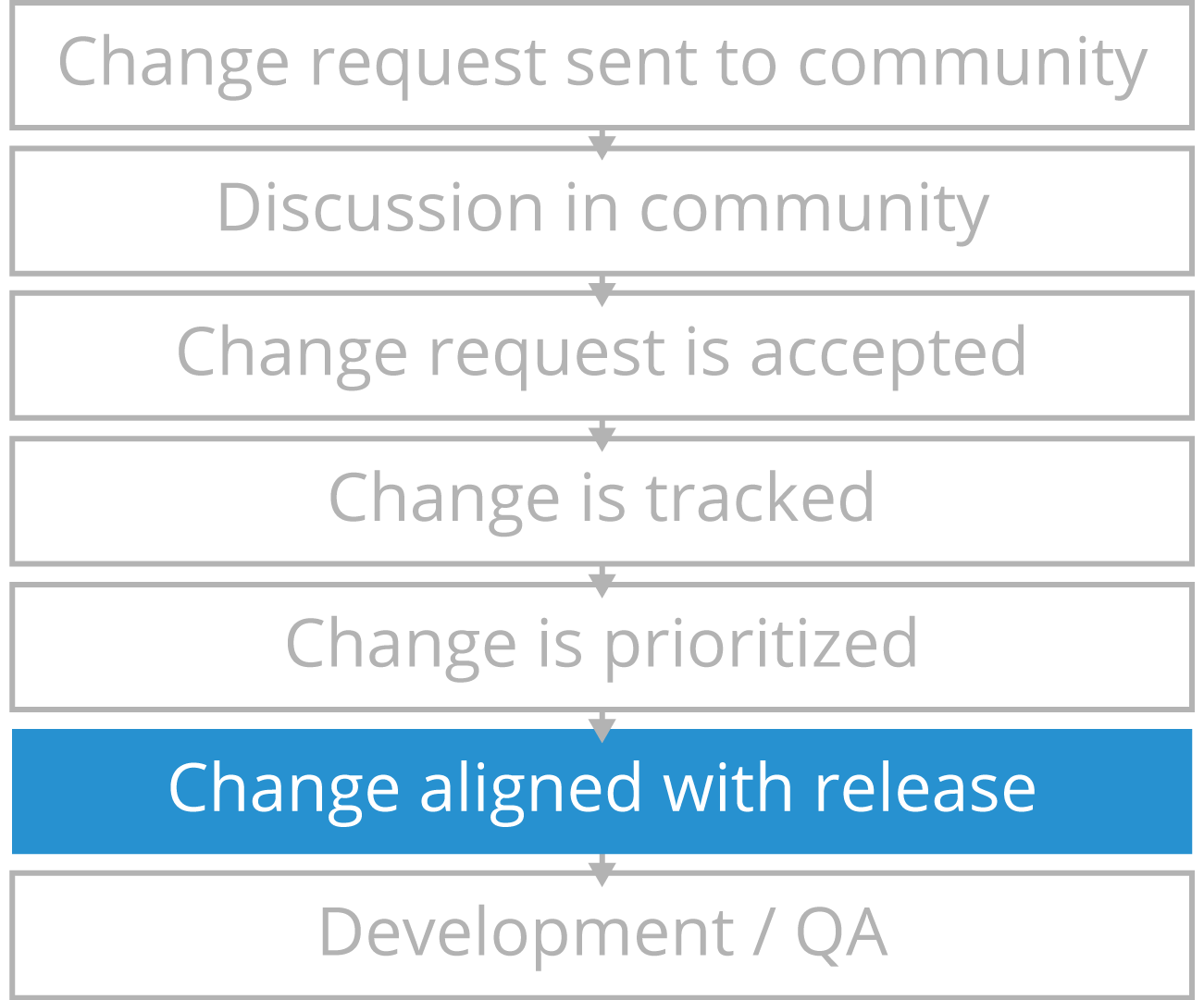

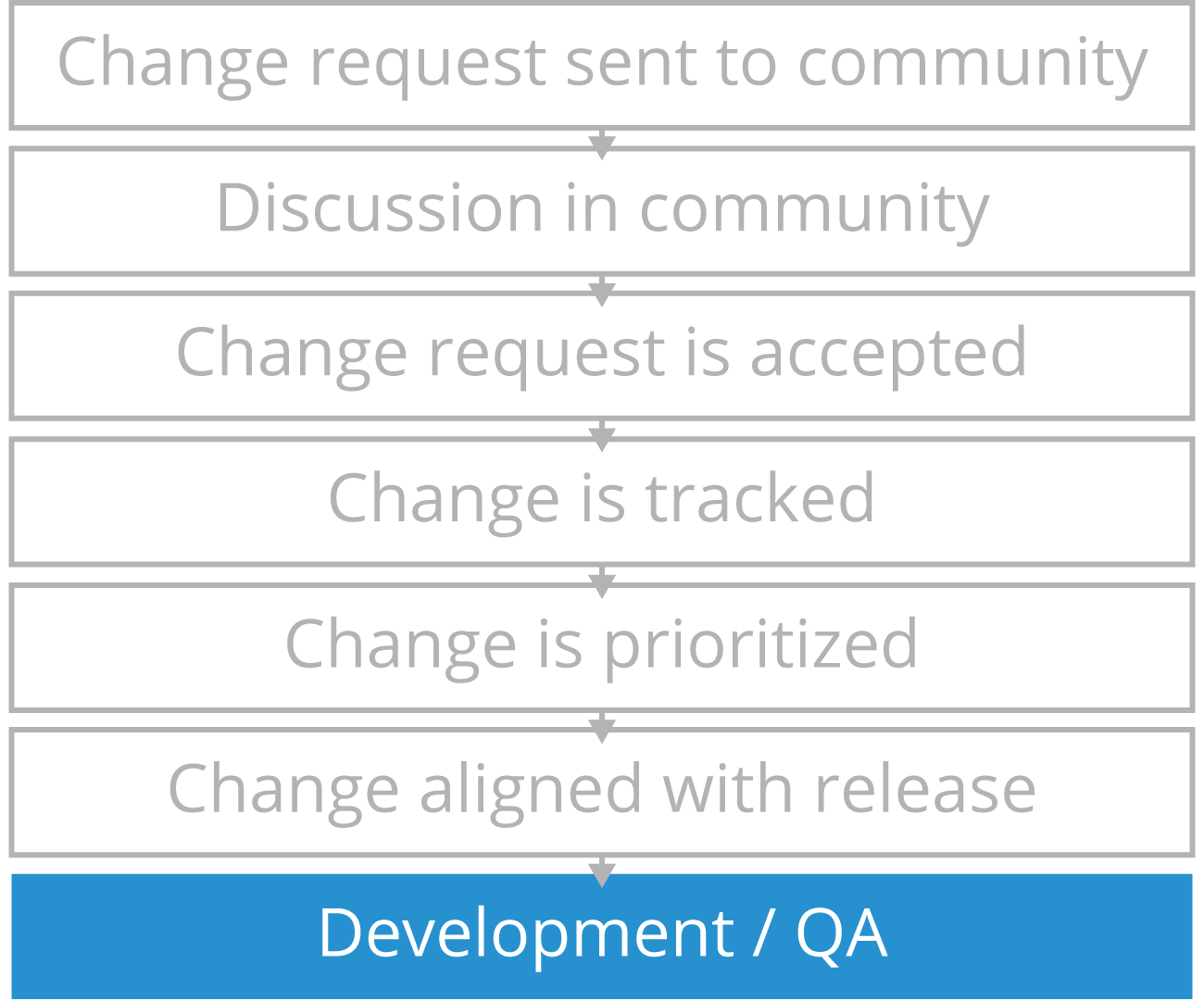

![]()

Once a change has been accepted, it needs to be tracked, and this usually occurs in some form of feature or bug tracking, depending on what tools are used by the project community. This tracking entry is considered the authoritative record of what was proposed and what was accepted as a change.

At this stage, the original submitting developer adds detailed feature information into the tracking tool so that a record is maintained of what subsystems the change will affect and what the overall plan for implementation is.

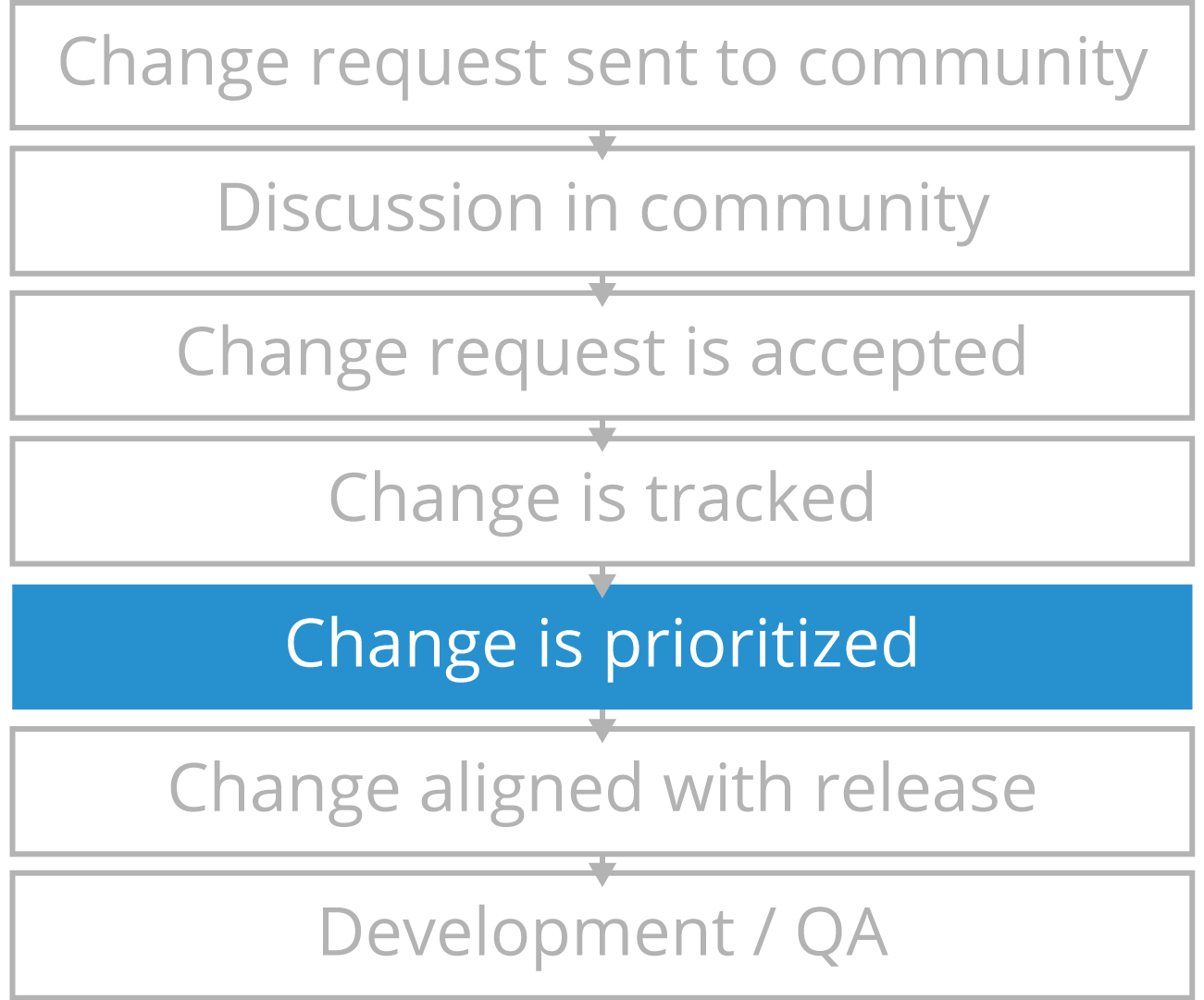

Prioritization

After a change has been accepted and tracked, its acceptance needs to be prioritized in conjunction with all other pending changes to the project. At this point, maintainers get involved again to prioritize which incoming changes are core to the project, and which are needed right away versus which can be accepted later.

Because maintainers generally have a global view of dependencies and future releases, they can work to prioritize changes and align features correctly. However, if a change is minor enough, or doesn’t touch too many core parts of the project, they may signal they are ready to accept it as soon as it’s ready.

Release Planning

Once a maintainer has completed prioritization of the incoming change, they will work to communicate the original developer who submitted the change request (as well as the entire community) on when they will be ready to integrate the change. This helps the maintainer and community plan for a manageable number of features per release.

During this phase, the original submitter will get notification of what specific future release their change is planned for.

Development & QA

After all of the prerequisites in the process are completed, the actual development and Quality Assurance can take place, where the developer and any other resources recruited from the community step in and begin to implement the new change, targeting the specific release set by the maintainer.

If for some reason the development runs into issues or it looks like they won’t be able to make the specific release window they were assigned to, it’s important for them to communicate early with the maintainer and community so that any dependencies on their change can be adjusted in the upcoming release cycles.

Lesson: Aligning Internal Processes

Where to Start

It’s important to consider how to best align your internal development processes to be more effective when you are contributing changes back to an upstream community. While you may still have unique development processes for internal or closed source software products, being able to shift contexts and work effectively when collaborating with upstream open source projects is important both for your upstream contributions, but also to help you most effectively consume the open source projects into your internal code.

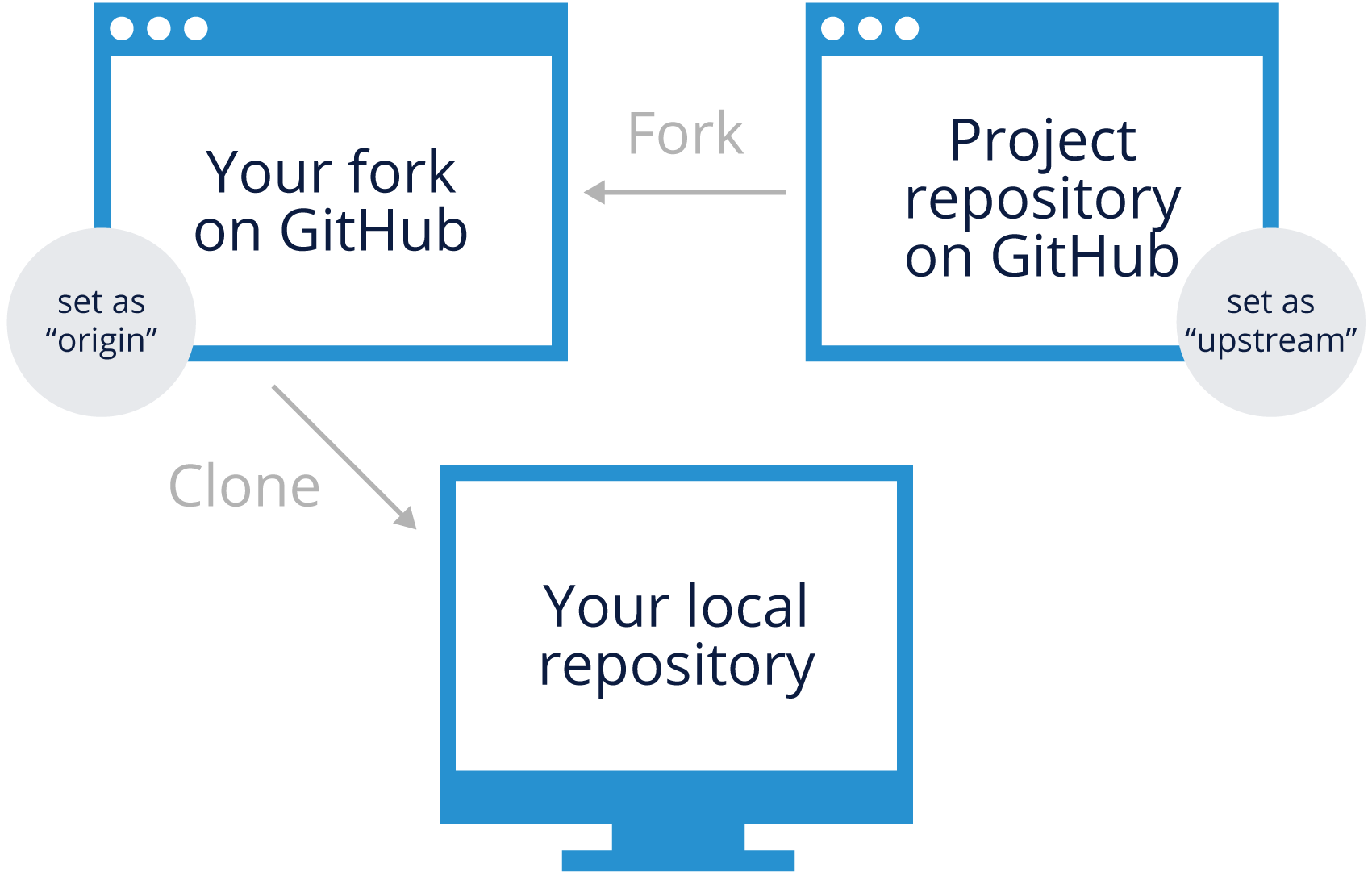

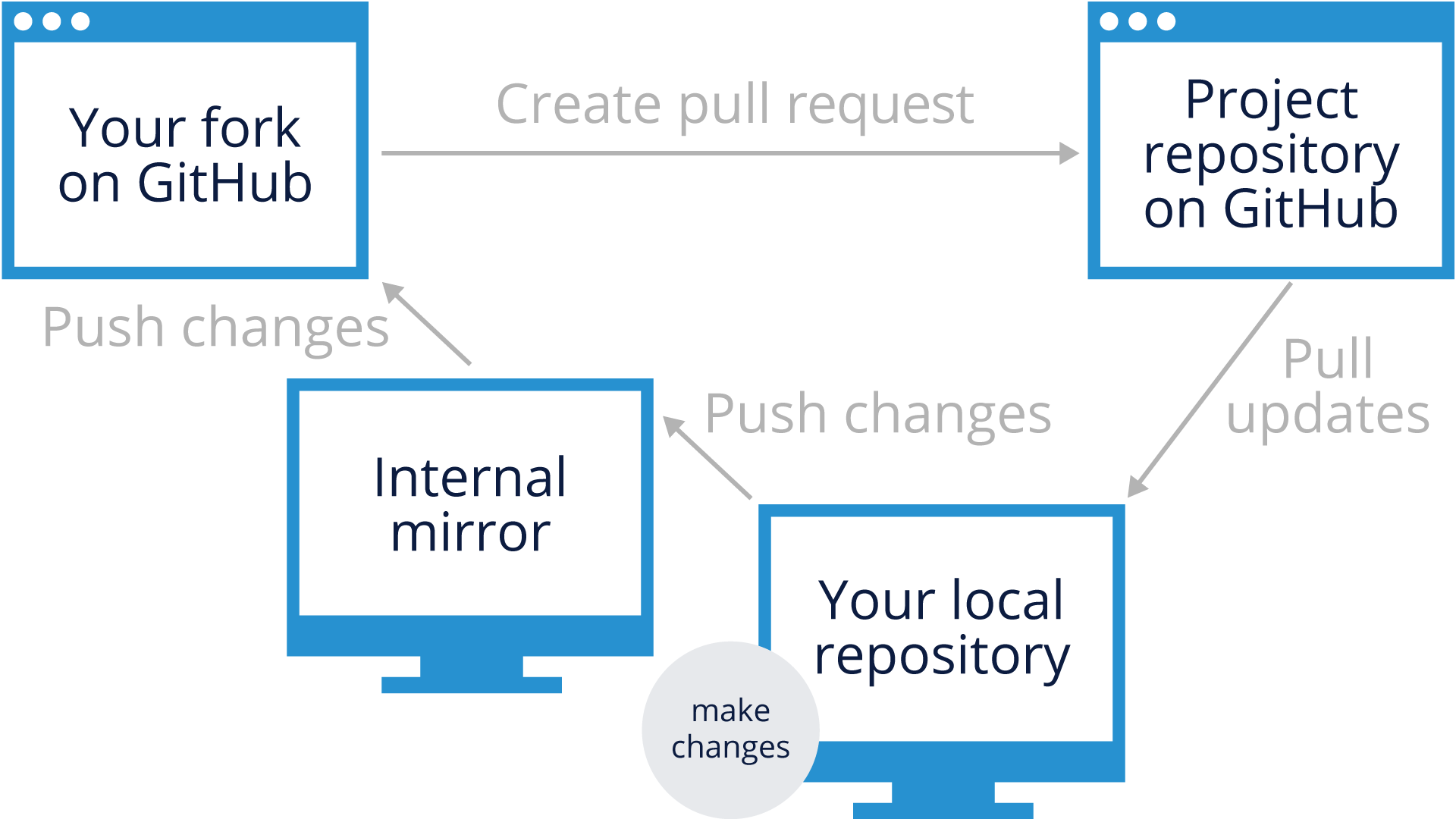

To get yourself setup for a contribution, you generally follow the process outlined below (this example is from Github, but can be generalized to any system utilizing git as the source control system):

If this is a small open source project or one that is unlikely to be used by others in your organization, you can generally leave the fork on Github in your own account, but if it’s likely to be used by other teams in your organization, you may want to fork the upstream project into a company-owned organization for easier maintenance.

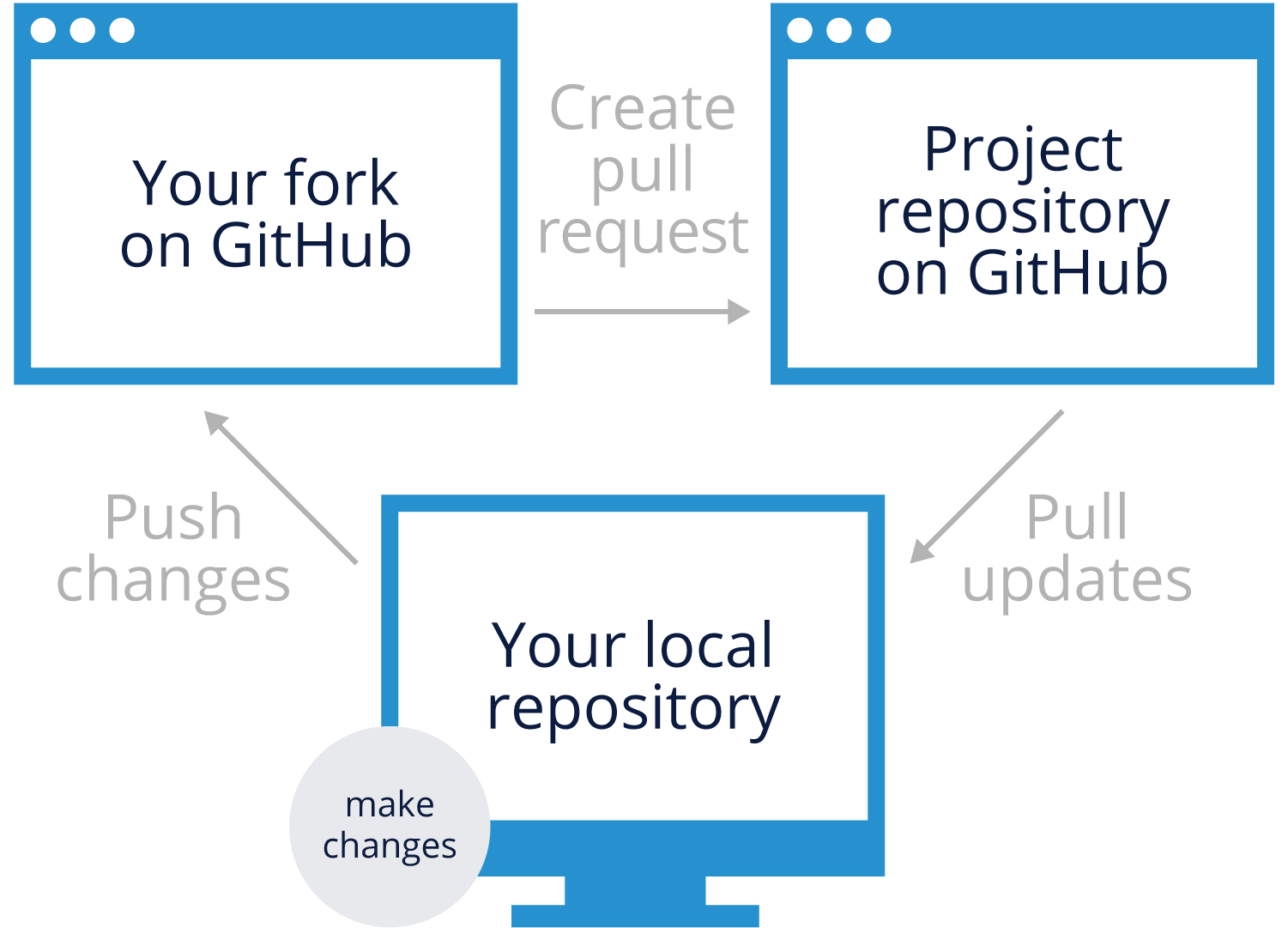

Once you’ve done the initial setup, the general workflow of pushing changes up through “pull requests” looks like this:

Internal Mirrors

For some organizations, especially those that have potential concerns about the long-term availability of open source repositories on the Internet, it may make sense to have an additional layer of repository structure inside your organization. For example:

Additionally, for some orgs, the “comfort factor” of having this internal mirror of an open source project gives them the ability to more easily have legal sign-off on usage of open source in products.

While it does provide a layer of safety, it does also increase the workload for changes going upstream, as you’ll need to push those changes from your local developer repo to the internal mirror, and then on to the actual fork on Github before proposing your pull request.

Internal Collaboration

Whether you choose to have your consumption of and contribution to upstream projects happen with or without an internal mirror, you’ll still need to build communication and collaborative practices within your organization to make sure that:

- You’re working on a small set of approved versions of the upstream project

- Changes you’re making are not redundant or in conflict with your internal teams

- Changes that you’re proposing to the upstream project are consistent across the company

Coordinating Upstream Pull Requests

If you have multiple teams consuming and potentially making changes to an upstream open source project, it’s important that you work to coordinate any changes that are being made to that project. Whether you monitor and prioritize/clarify those changes in an internal mirror repo, or your public organizational repo, it helps to identify internal “maintainers” inside of your organization that have a responsibility for acting as an intermediate “upstream” review team.

Effectively coordinating your upstream project contributions in a large engineering organization can seem like a lot of extra work, but it’s needed if you want to keep the upstream project effective and healthy so you can rely upon it, and, also so that your organization’s reputation with the upstream community remains intact. Having many conflicting changes from a single organization going to the upstream project can have a detrimental effect on how your organization is viewed by the open source community, which negatively affects your ability to work with them long-term.