module-eoss-ospo101

Section: Introducing Open Source

Lesson: Introduction

Section Overview

In this section, we will provide definitions of open source, open standards and closed source software, as well as comparisons between them. We will also provide an overview of how these three elements are used together to deliver technology solutions that we all rely on.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you should be able to:

-

Define open source, open standards and closed source software.

-

Explain the differences and similarities for all three concepts.

-

Understand how all three concepts work together.

Lesson: Definitions

What is Open Source Software?

According to Wikipedia:

Open source software (OSS) is a type of computer software in which source code is released under a license in which the copyright holder grants users the rights to study, change, and distribute the software to anyone and for any purpose. Open source software may be developed in a collaborative public manner.

Let’s break down this definition and explore it a bit:

Computer Software

Computer Software refers to a program or firmware written by an author. The author of the software can be one or many people, and possibly doing the work on behalf of a company. The program is runnable on a particular computer through a machine-readable format that is achieved through conversion of ‘source code’ to what is known as ‘binary format.’

Source Code

Source Code refers to the human-readable set of instructions used to represent an algorithm or idea for a computer to execute. Many computer languages can be used to write source code, which will get converted to machine-readable binary format through the process of compilation or real-time interpretation. Having the source code allows you to study and efficiently modify the software.

License

License is a legal document that records and formally expresses a set of legally enforceable acts, processes, or contractual duties, obligations, or rights related to the software and/or source code.

Study, Change and Distribute

A fundamental component of open source software is the freedom granted by various open source licenses allowing individuals to study the software, change it for their own purposes, and then redistribute their changes to anyone else for any purpose. The requirements placed on the changed version vary depending on the type of open source license used. More details will be provided on this in later modules in this course series.

Collaborative Public Manner

Collaborative Public Manner is important here because the freedoms provided by the license allow for large and diverse communities to form around popular open source software, helping drive innovation and allowing companies to both contribute to and reap the benefits of these software projects. Linux is a key example of one such community, but there are many others like the Apache Web Server, Kubernetes and OpenStack.

What is Closed Source Software?

Software that is not open source software is closed source software. Here’s an explanation of what the closed source software is based on the Wikipedia definition:

Closed source software, also often referred to as proprietary software, is non-free computer software for which the software’s publisher or another person retains intellectual rights beyond those allowed for open source software— usually copyright of the source code but sometimes also patent rights.

As before, let’s unpack this definition a bit and explore some key elements:

Closed Source

In contrast to open source, closed source software’s human-readable instructions are not made available by the author or authors of the software. What is delivered and installed on a computer is the machine-readable format only. Popular programs like Microsoft Office, for example, are delivered this way.

Non-free

Non-free here refers to the fact that the author(s) distribute it under a license that is not open source software, that forbids studying, modifying or redistributing the program to anyone. There may or may not be a fee for its use.

Intellectual Rights

The author(s) retain access not only to the source code, but also to the ideas and/or algorithms used to design the program.

The other main distinction here is that closed source software is designed and developed by teams of developers (usually working for a corporation, but not always) who are typically not collaborating with outside community members (as is typically done with open source software).

What are Open Standards?

There are various definitions available for what an ‘open standard’ is, and we can coalesce pieces of them here:

Open Standards are publicly available and royalty-free, while ‘standard’ means a technology approved by formalized committees that are open to participation by all interested parties and operate on a consensus basis. An open standard is publicly available, and developed, approved and maintained via a collaborative and consensus driven process.

Additionally, Open Standards should not prohibit conforming implementations in open source software.

Let’s go ahead and dive a bit deeper here as well:

Publicly available

The standard is available to the public at no cost.

Royalty-free

This is an important distinction between open and non-open standards. This is the ability for anyone to utilize the standard to build a solution without having to obtain a license from an entity (or pay an entity) is paramount to wider adoption.

Collaborative and Consensus Driven Process

This should now be familiar to you from the previous definitions of open source, and it is also critical here as it allows for both a wider set of perspectives and also the best chance at broad adoption by a variety of companies and individuals. It also sometimes makes defining standards a lengthy process.

Conforming Implementations

This is a specific definition set forth by the Open Source Initiative (OSI), an industry consortium that helps maintain both approved open source licenses as well as the formal definition of open source. Their Open Standards Requirement (OSR) adds in this definition to further clarify that there should be nothing in the standard’s definition that would preclude someone building a piece of open source software that conforms to the standard itself. Abiding by this gives those who use the standard confidence that they will have both open source and closed source options to choose from when picking an implementation.

There are many standards that we rely on every day, including TCP/IP (the underlying standard for communications on the Internet), HTTP (the protocol behind the World Wide Web), HTML (the language used by web page authors to format content), GSM (the standard for much of the world’s cellular phone communications), ODF (the Open Document Format used to exchange documents between various word processors), and PDF (the Portable Document Format used to produce print-ready documents).

In many of those cases, there are open source implementations of these standards to allow many individuals and organizations to participate in helping build and advance these technologies.

Mixing and Matching

In today’s technology landscape, there is rarely a case where only one of these three elements (open source, open standards, closed source software) is used in isolation.

Most often, you’ll experience open source implementations of open standards (like the Apache Web Server’s implementation of HTTP), but you can also find instances of closed source software that implement an open standard, such as cryptography software companies who implement the Key Management Interoperability Protocol (KMIP) standard, allowing interoperability among many vendors, and even other open source software.

You’ll also see closed source software being used alongside open source software, as in the case of people using the popular open source Firefox browser on closed source operating systems like Windows and Mac OS X. Even open source operating systems like Linux are used to run closed source applications like stock exchange applications and other financial software.

Section: A Short History of Open Source Software

Lesson: Introduction

Section Overview

In this section, we will provide a brief overview of the roots of the free software movement, and the subsequent birth of open source software. We’ll include a discussion of how pragmatism vs. idealism played into open source becoming a critical component of business and technology strategies in organizations. There will also be a short discussion on the evolution of open standards play in this space.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you should be able to:

-

Explain how the Free Software movement gave birth to open source.

-

Describe how the notions of idealism vs. pragmatism affected the adoption of open source.

-

Articulate the evolution of open standards and the role they play in this ecosystem.

Lesson: Free Software & Open Source

A Long and Storied History

Sharing of software has gone on since the beginnings of the computer age. In fact, not sharing software was the exception and not the rule. The concept of Open Source Software (OSS) long predates the use of the term. For a detailed history of the early days of software, there are many resources you can check, including Wikipedia, but we’ll give a condensed version here. It’s important also to note that there are many disagreements about certain details of this evolution, but it’s important to understand the basic timeline.

In the early days of computing (1950s-1960s), software was produced mainly by academics and corporate researchers working for early computer companies. It was difficult and time consuming to write, and generally shared as works of public-domain. These works are not owned by an individual author or artist. Anyone can use a public domain work without obtaining permission, but no one can ever own it. The software was not seen as a commodity in and of itself, as it required the specialized (and expensive) computer hardware to even run.

In the late 1960s, things began to change, as computer operating systems and compiler technologies began to make it less cumbersome to build effective software that ran on a variety of computer platforms. This led directly to the rise of software-only companies, and with software gaining the right to be copyrighted in 1974, the die was cast for software to become an important commodity that these companies fought to protect.

The late 1970s and early 1980s saw the increasing trend of only distributing machine-readable code without the associated human-readable source code. In the early 1980s, MIT researcher Richard Stallman began a project to write what would become the GNU operating system (which would later inspire the popular Linux kernel). During this time, he established the Free Software Foundation and wrote the Free Software Definition in an attempt to wrest control of software created at MIT back from corporate interests who had changed and co-opted it.

The Free Software Foundation’s other main claim to fame is the creation of the GNU Public License (GPL), which used the notion of ‘Copyleft’ to require any changes made to Free Software to be made available to the user receiving the free software. Linus Torvalds (creator of the Linux operating system) released his first kernel in 1991, licensed with the GPL. As we now know, it has become the basis for a significant portion of the world’s technology.

In 1997 Eric. S. Raymond published The Cathedral & The Bazaar, an analysis of the former academic hacker community and free software principles, which led to a strategy meeting in 1998 of several industry and free software individuals, including Christine Peterson, who coined the term ‘open source software.’ In the next section, we’ll examine the reasons for this change in ‘brand.’

Pragmatism vs. Idealism

At the heart of the naming debate between ‘Free Software’ and ‘Open Source Software’ is an oddity in the English language. Specifically, the two different meanings of ‘free’:

-

Free as in free speech, freedom to distribute.

-

Free as in no cost, or as is often said as in “free beer”.

Christine Peterson and the others involved in advocating for ‘open source’ were attempting to clarify the concept of free here - making it clear that the source code would be open for inspection, redistribution and modifications. As more corporations became involved with these software ecosystems, open source gained traction, in large part due to the perception that ‘free’ software didn’t have as much value as ‘professionally’ developed code. In reality, the amount of quality open source software has only continued to increase, and much of it is professionally developed.

With more corporate involvement though came a bifurcation in the world view of Free Software Foundation advocates and the open source community. Specifically, this centers around idealism vs. pragmatism.

Idealism

Here “free” means as in freedom, not beer. There is a profound belief that all software should be open for ideological and ethical reasons, not just technological ones.

Pragmatism

Here the primary considerations are technical ones including faster and better development involving more contributors and reviewers, easier debugging, etc.

It’s important to note the more ideological perspective has strong technical imperatives as well, and in many cases the objectives of both streams coincide. For example:

-

Should the software powering a life-saving medical device (such as a pacemaker, or an insulin pump), be secret? Do we not have the right to know what is controlling such devices? How do we know they are not vulnerable to external attacks that can kill us?

-

Should the software powering voting machines be closed? How can we be sure we can respect the integrity of tabulated results? This is particularly true when experiment after experiment has shown closed source voting machines to be full of security vulnerabilities.

Unfortunately, the conflicts between these two attitudes towards open source have often been acrimonious and destructive. It is unlikely to ever end; but it’s important to note the pragmatic approach has most of the economic resources behind it due to corporate buy-in, and the more philosophical camp will always have determined adherents. The vast majority of the work in open source happens somewhere between these two extremes, but it’s important for each to exist to provide valuable boundaries.

The Evolution of Open Standards

In many ways, the evolution of standards mirrors that of free software to open source. In this case, three kinds of standards began to evolve—closed standards, de facto standards, and open standards.

Closed standards are not publicly available, require implementers to pay royalties to third parties, or both. For example, most common wireless standards the average person recognizes, including 4G, Bluetooth, or WiFi are closed standards. These standards have specifications that are restricted either by access or intellectual property terms.

As the software market began to grow, and the kinds of problems customers were solving became so large that they required multiple areas of speciality, it became apparent that interoperability was going to be a key requirement for businesses of all kinds.

Customers began to pressure vendors to allow for heterogeneous systems that brought best-of-breeds solutions to bear on their problems. To make this possible, open standards began to develop, allowing many people to collaborate on ways of effectively moving data between and among applications and systems. Some open standards didn’t start as intentional standards. Some started as open source projects that through widespread adoption became de facto standards. The most common example is the Linux kernel which has become a *de facto *standard for classes of devices, such as in high performance computing where Linux powers 100% of the world’s Top 500 Supercomputers.

There are too many open standards to list here, but you can find a reasonably good list on Wikipedia. Perusing that list you’ll find ones that you probably know about (TCP/IP, PDF), as well as others you probably rely on but didn’t know as much about (HTML, USB).

History is Always Happening

The main reason for providing this historical background is that it both informs what has come before, but also symbolizes that nothing is ever static in the software and technology industry. There will always be questions of balancing the idealist aspects of free software with the more commercial values of pragmatism.

There is also a growing movement around thinking about the ethical aspects of computing and how that affects everything from licensing, to intellectual property and collaboration models.

Understanding where we’ve come from in open source and open standards will give us the context to properly evaluate where we need to go in the future.

Section: Reasons to Use Open Source

Lesson: Introduction

Section Overview

In this section, we will give an overview of how the community and collaborative model of open source ensures continued efficient development of enterprise-grade software. We’ll also discuss some potential ways to effectively marry open source with open standards for increased value.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you should be able to:

-

Describe the community and collaborative model of open source.

-

Articulate solid business reasons why open source provides value for enterprises.

-

Explain how open source and open standards can be combined to increase the overall value of a technology solution.

Lesson: Why Should I Use Open Source & Standards

What Is an Open Source Community?

There is not some mythical ‘open source community’ that magically makes all open source development happen. There are many different open source communities, with many different types of cultures. However, the community construct harkens back to the earliest days of computers, rooted in the academic/corporate/sharing/hacker mentality. Almost all communities have the following main characteristics:

-

Geographic distribution of development resources.

-

Decentralized decision-making capabilities.

-

Transparency of both development and decision making.

-

Meritocracy - influence is earned through sustained valuable contributions.

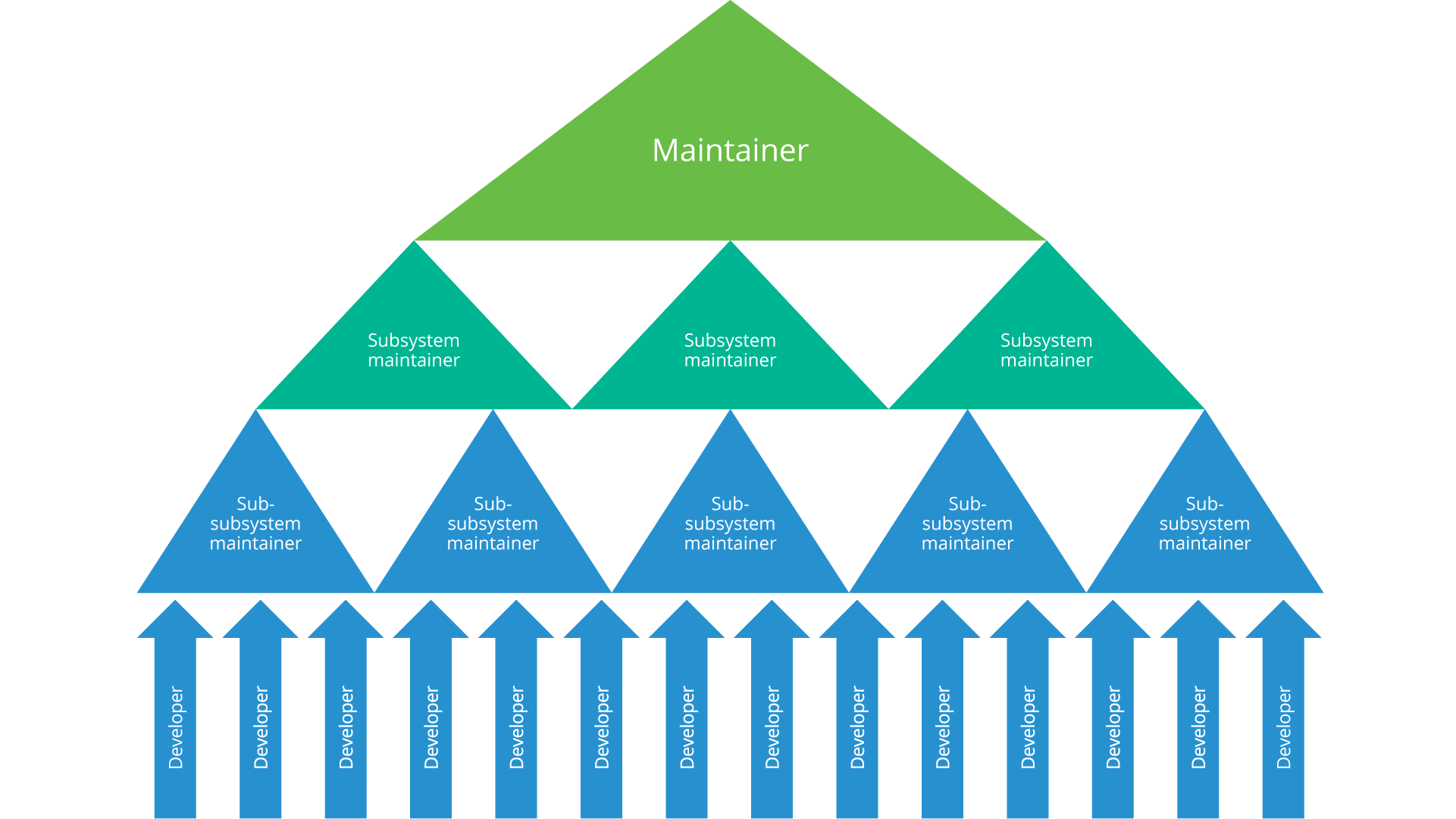

In addition, most communities exhibit a tight vertical hierarchy, with loose horizontal structure, which allows small changes (the lingua franca of open source) to flow upward, passing through many rapid review cycles that provide a significant set of ‘checks and balances’ that help ensure software quality.

An example community organizational structure:

How Does This Model Differ from Other Development Models?

While modern software development teams inside of technology corporations can share some of the ‘agile’ principles illustrated above, they generally have some significant differences. These differences are neither good nor bad, and often exist for very good reasons. They do, however, provide a challenge for organizations as they begin the journey toward more open source community participation.

Here are some of the most significant practices of open source software projects that are different from corporate development teams:

-

Influence and stature are not conveyed by title or position - meritocracy rules the day.

-

Transparency in both source code and decision making is paramount - no side conversations or decisions.

-

Support for geographically-distributed teams is built in - asynchronous modes of communication and culture are the norm.

Some organizations have applied lessons from the open source community to their own internal efforts (a practice known as ‘Inner Source’) to take advantage of the speed and flexibility they offer. Doing this can also help build the necessary institutional culture that allows for easier engagement with the upstream open source ecosystem.

The Business Perspective

Now that we’ve covered a bit of what the community development model looks like, let’s look at some reasons that businesses of all sizes have chosen open source as a valuable technology tool to help them solve real-world problems.

Open source usage within an enterprise provides the following advantages:

-

Speed

-

Lower Cost

-

Customizability

-

Innovation

-

Security

-

Business Advantage

-

Flexibility in licensing

We’ll cover each of these in the next few sections.

How Does Open Source Speedup Development?

Open Source Software has proven instrumental in speeding software development cycles. One of the most striking examples is in the mobile device market where we are seeing major new products being released in 6-12 month cycles. Open source is essential to fast evolutionary delivery.

So exactly how does open source speed up development?

-

Open Source software acquisition is often faster and easier – no purchase orders, contracts, SOW or license negotiations to get started.

-

Open source deployments are usually much quicker. Unlike commercial installation, configuration, and implementation cycles which are often too long and cumbersome, open source comes from a download-and-go culture.

-

The leading open source projects are evolving faster with community driven features, instead of revenue driven management. Fast decision making in open source (often a form of lazy consensus) enables projects to incorporate new features and fixes very rapidly.

-

Because it is subjected to broad community testing, mature open source is often of higher quality. In fact, software quality met or exceeded expectations 92% of the time according to a Forrester Research study.

-

Open source supports customization with the source code, a collaborative community, interfaces and tools.

-

With an evolutionary delivery approach, open source is usually up and running in hours instead of weeks or months.

Why Is Open Source Lower Cost?

Using open source software can significantly reduce development costs in a number of proven ways:

-

A recent Red Hat study has shown that open source has a 30% lower total cost of ownership compared to commercial/closed source solutions.

-

With open source you can avoid functionality overkill. Many closed source products have an overload of capabilities that clients rarely use, need, or even want. And they are often bundled so that they must be paid for anyway.

-

Open source helps prevent vendor lock in and promotes competition. Even where commercial open source vendors are utilized, you have the freedom to switch vendors or even drop support without changing your application.

-

Open source also helps with consulting, training and support costs because there is no exclusive access to the technology. You can often multi-source support from vendors or even receive support from a vibrant community of developers. Many companies hire developers from the community to support their implementations, and contribute fixes back to the upstream project.

-

Active communities often provide higher quality support than commercial support agreements, and what’s more, it’s free.

Why Is Open Source More Flexible?

Open source offers the most flexibility of any 3rd party software alternative:

-

With open source you are never locked into a vendor, their costs, their buying structures or their re-distribution terms. Open source enables vendor independence and competitive options.

-

Open source often has very liberal contractual limits on deployment, if any, so you have the greatest possible flexibility on platforms, numbers of users, number of processors.

-

Because you have access to the source code, you may create any customizations you need, and if they are of value to others, the community may support them in a future release.

-

Open source communities encourage and facilitate customization making it easier to extend the solution for particular use cases or to integrate with other products.

-

Healthy open source communities provide ongoing support and encourage input and suggestions for improvements.

How Does Open Source Support Innovation?

Open source software was originally conceived as a way to facilitate development and innovation through collaboration.

The open source approach has proven so effective for innovation that many leading edge software technologies are driven by open source communities. For instance:

-

The Internet has been developed primarily as a large collection of open source projects.

-

Software development tool innovation and integration is largely an open source domain.

-

The incredible rate of innovation in the mobile communications space is only possible through open source. Although Android is the primary example, even closed source platforms like Apple’s iOS are largely built using hundreds of open source software libraries and components.

-

Like the rest of the Internet, social media software platforms have emerged from and grown through open source software.

-

The arena of scientific computing and massively parallel computing are almost exclusively open source domains.

Many open source communities exhibit rapid evolution that can be harnessed through participation to speed your own innovation. The open source ethos of bottom-up meritocracy directs ownership and accountability back to development teams

One of the best ways to introduce a new software idea, test new capabilities and grow an active user base is through an open source community

And finally, the innovation that open source enables is not just technical innovation. The lack of contractual constraints in open source licensing allows for creative new uses, new distribution schemes, flexible and creative packaging and pricing approaches and other forms of business and market innovation.

What are the Security Advantages of Open Source Software?

Unfortunately attackers are targeting and attacking software systems around the world. Neither open source software nor closed source software is always more secure. Security depends on many factors, such as how the software was designed, implemented, verified (including testing), and deployed.

However, open source software does come with a potential fundamental security advantage over closed source software. One of the key principles of secure software design is “open design”, that is, secure software design should presume that everyone knows how its protection mechanism works. Doing this enables mass worldwide peer review to find security vulnerabilities and fix them before the software is deployed.

Of course, potential is not always realized. To be secure, open source software projects must be developed with security in mind, actually be reviewed, and have those problems fixed before the software is deployed. Many open source software projects already take steps to employ this potential advantage, and the Linux Foundation is working with various open source software projects to help them take advantage of it as well.

How Does Open Source Provide a Business Advantage?

All of the factors above add up to a software competitive advantage for your organization.

-

In today’s rapidly evolving markets, the company that consistently produces software solutions the most quickly at lowest cost will win.

-

At this point, open source software has become such a mainstream phenomenon that not using open source effectively will almost certainly place your organization in a disadvantaged position.

Research firm Gartner had this to say about open source:

“Open source is ubiquitous, it’s unavoidable… having a policy against open source is impractical and places you at a competitive disadvantage”

As a recent McKinsey & Co. report described, the “biggest differentiator” for top-quartile companies in an industry vertical was “open source adoption,” where they shifted from users to contributors. The report’s data shows that top-quartile company adoption of open source has three times the impact on innovation than companies in other quartiles.

Bridging Open Source and Open Standards

There has been a growing trend in the last several years of both the standards world and the open source ecosystem attempting to find better ways of working together. While there are sometimes challenges (primarily around the execution speed mismatch of the two groups), there are many good reasons to continue to advocate for a closer relationship between the two.

There are some good examples of projects where this is or already has worked:

-

The Linux Foundation’s JDF (Joint Development Foundation) efforts - GraphQL among others.

-

OASIS Open’s Open Cybersecurity Alliance, which is providing open source reference implementations of existing open standards for sharing cyber threat data.

-

IETF’s mantra of “rough consensus and running code” has led to many open standards collaborating with open source projects such as OpenDaylight, OPNFV, OpenStack, and others.

Standards and open source move at different paces, and work on interoperability in different ways, but being able to build open source implementations of open standards helps drive more open source usage in customer supply chains that have traditionally relied primarily on standards - areas like government, finance and NGOs, for example.

Additionally, by supporting standards, the open source ecosystem gets the ability to interoperate even with closed source software, which provides businesses with more choices and more flexibility.